SPA/AAP Meeting Reviews

Friday Session I: You Take My Breath Away

Reviewed by Zulfiqar Ahmed, MD

Anesthesia Associates of Ann Arbor

Oakwood Hospital System

Dearborn, MI

Dr. Butch Uejima (Lurie Children’s Hospital) moderated the first session, “You Take My Breath Away”. Addressing the subject “Cystic Fibrosis – What’s New for the Anesthesiologist”, Dr. Pamela Zeitlin (Johns Hopkins) delivered a thorough overview of the molecular pathology of cystic fibrosis and a detailed description of chloride channel malfunction. The genetic pathology of CF is characterized by mutation of Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR) gene.

Dr. Butch Uejima (Lurie Children’s Hospital) moderated the first session, “You Take My Breath Away”. Addressing the subject “Cystic Fibrosis – What’s New for the Anesthesiologist”, Dr. Pamela Zeitlin (Johns Hopkins) delivered a thorough overview of the molecular pathology of cystic fibrosis and a detailed description of chloride channel malfunction. The genetic pathology of CF is characterized by mutation of Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR) gene.

She elaborated that the clinical triad suggesting diagnosis of Cystic Fibrosis (CF) includes: elevated sweat chloride, pancreatic insufficiency and chronic pulmonary disease. Sweat test diagnosis by pilocarpine iontophoresis shows more than 60 mEq/L chloride. However, this test is inaccurate in the first month of life. Other causes of elevated sweat chloride include untreated hypothyroidism, glycogen storage disease, Addison’s disease and Ectodermal dysplasia. Important clinical features of CF include multisystem involvement and MRSA colonization. Survival rates are improving, diabetes is more commonly diagnosed in CF patients, and advances in molecular control drugs are being made.

Preoperative evaluation of the patient with CF should include enquiry about parental assessment of presence of acute illness, malaise, dyspnea, weight loss, fever, increased sputum, night cough and diabetes. Symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea and GERD should be solicited. Physical exam should look for presence of wheezing. Oropharyngeal or sputum microbiology, resting oxygen saturation, capnography and a recent chest radiograph should be reviewed. Medication review with attention to corticosteroid and antibiotic use is important.

An alarming trend is the increased prevalence of MRSA in CF patients from 2.1 in 1996 to 25.9% in 2011. CF patients may use a wide variety of medications including Dietary Salt (high sweat chloride), Dnase (reduce airway secretions), antibiotics (chronic lung infections), anti inflammatories, pancreatic enzymes, stool softeners (ileus), insulin (islet cell loss) and bile acid salts (hepatic insufficiency).

The most recent FDA approved drugs for this patient population are CFTR modulator therapies such as Ivacaftor (Kalydeco). An example of the efficacy of Ivacaftor is that it has shown weight gain improvements of 2.8 kg at week 48 of treatment compared to placebo. This is a significant improvement in CF management but comes at high financial cost.

Dr. Linda J. Mason (Loma Linda), spoke on the topic “Advances in Managing Asthma during the Perioperative Period”. 4-9% of children in the U.S. are affected by asthma, a disease characterized by airway inflammation, smooth muscle hypertrophy, edema, mucous plugging and plasma exudation with shedding of epithelium and cilia. Adult and pediatric asthma are different diseases. In children 50% of total airway resistance is in peripheral airways compared to 20% in adults.

Leukotriene Pathway Modifiers such as Singulair are the first new drugs in 20 years for the treatment of asthma. Singulair is especially effective as a first line therapy in exercise and aspirin induced asthma and may be chosen before inhaled glucocorticoids. Hypothalamic pituitary axis suppression may occur with beclomethasone > 800 ug or equivalent.

Data indicates that asthmatic children are 5.5 times more likely to experience wheezing perioperatively than non-asthmatics and are more likely to have perioperative respiratory complications. In patients with severe asthma with frequent or recent asthma exacerbation, oral prednisone 1 mg/kg (60 mg max) for 3-5 days prior to surgery or oral dexamethasone 0.6 mg/kg (16 mg max.) or methylprednisolone 1mg/kg for 48 hours prior to surgery is recommended. With regards to the use of inhaled agents, data from von Ungern-Sternberg et al has shown that Desflurane increases airway resistance in patients with susceptible airway such as Asthma or URI.

It may be safe to use acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and ketorolac in most patients with asthma but caution is needed in asthmatic patients with nasal/ethmoidal polyposis and aspirin sensitivity (Samter’s triad). It may be wise to avoid ketorolac in severe asthmatics. Data has shown that albuterol delivery to the lungs by MDI through 3.0-6.0 mm ID tracheal tube is low (2.5-12.3% of discharged dose). This delivery may be increased 10 fold by actuating the canister into a distally placed catheter via the ET tube. Infusion pump tubing can also be used for this purpose.

This mode of administration may also increase toxicity if the physician is too aggressive. Hence it is advisable to administer only one puff at a time with puff to puff intervals 2-5 min apart. Maximum cumulative puffs should equal 1 per 5 kg patient weight and continuous ECG monitoring for heart rate changes and arrhythmias should be performed.

The intraoperative management of bronchospasm includes IV corticosteroids (methylprednisolone1-2mg/kg or hydrocortisone 1-3 mg/kg), IV lidocaine, 1.0 to 1.5 mg/kg and/or atropine 0.02 mg/kg. Sub Q epinephrine 10μg/kg, terbutaline 5-10μg/kg or IV epinephrine or isoproterenol are also appropriate. Ventilation should be managed by pressure-controlled ventilation with low inflating pressures and prolonged expiratory time.

The topic “New Ventilation Modes - The Path to Optimal and Safer Ventilation” was addressed by Dr. Jeffrey M. Feldman. (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia). Small errors in ventilatory strategies may be significant with potential for injury or inadequate ventilation. Small volume variations can be a significant percentage of intended volume leading to hypo/hyper ventilation and volu/barotrauma.

One goal of ventilation in any patient is accurate volume delivery to the airway independent of circuit compliance and fresh gas flow. To obtain this goal in children, pressure controlled ventilation is most appropriate. Volume controlled ventilation in small children is inaccurate as circuit compliance, fresh gas flow and circuit leaks make appropriate ventilation unreliable. During the machine check, compliance compensation can add volume to insure set volume delivered to airway.

In small children, changing circuit length after compliance test will change the circuit compliance. If the circuit compliance is decreased, one risks hyperinflation. If the circuit compliance is increased, one runs the risk of hypoinflation. Adding a humidifier or re-expanding the circuit can counter this. Hence it is recommended to perform leak and compliance tests with the circuit configuration one intends to use.

Dr. Feldman questioned the need for ICU ventilators in the operating room. They do not offer advanced modes of ventilation compared to modern anesthesia ventilators and fail to deliver better pressures or volumes. ICU ventilators cannot deliver volatile anesthetics and transitioning to manual ventilation can pose practical challenges.

Pediatric patients are especially susceptible to increased dead space. Small changes in dead space can cause significant changes in VD/Vt. Consequently, apparatus dead space should be carefully managed. Data has shown that in low weight babies, a few milliliters of dead space ventilation cause significant elevation of PaCO2. Emerging data has suggested that small tidal volumes with PEEP and other recruitment strategies have lung protective effects. Due to limitations in tidal volume measurements less than 20 milliliters, this may be challenging in babies weighing less than 3 kg. Square wave pressures may improve gas exchange in difficult to ventilate patients.

According to Dr. Feldman, an “Optimal Ventilation Strategy” includes the following key elements:

- Avoid 100% O2 without PEEP during induction and emergence Consider ARM + PEEP when using 100% oxygen

- Use small tidal volumes (6-8 mls/kg) with PEEP

- Use of compliance compensation correctly

- Use PEEP liberally during controlled ventilation

- Minimize dead space

- A volume targeted mode is desirable

- Consider spontaneous ventilation if pressure support is available

Friday Session II: Strength, Courage and Wisdom

Review by Anuradha Patel, MD, FRCA

Rutgers New Jersey Medical School

This session was very different from other panels and was probably a first for the SPA meetings. Learning from our patients: two patients with chronic disorders and/or disabilities came to tell their story. The first speaker was Katherine (Kasey) Seymour who has been battling Cystic Fibrosis for 18 years. She was diagnosed with CF at age 4 1/2 years, has undergone 11 surgeries, and has been in and out of the hospital many times.

Kasey related her experiences with anesthesia. Her first surgery was at 10 years old when she needed a port. Not unexpectedly, she was scared and anxious. But, the team taking care of her was wonderful. They gave her premedication and she told the story about how people can’t keep secrets under the influence of sedative/anxiolytic medications.

Her surgery was two days before Christmas and her mom was trying to distract her from the impending procedure and was talking about presents, when Kasey revealed what her dad got her mom for Christmas. She felt that her first surgery was a relatively positive experience, but subsequent surgeries have not been so good. She recalls that waking up was not fun, particularly emerging from anesthesia not feeling her usual self. There was a horrible beeping and screeching, possibly from the monitors.

Now, over the years, her lung functions have deteriorated up to 30 percent. On one occasion, surgery was cancelled after anesthesia was given to her, but recovery took a long time. She had three days of headaches and again felt like she was not her usual self. Now, she gets shooting pains in her head and neck and it takes two weeks to fully recover after any procedure. Her biggest concern is that she will need more surgeries and at each encounter she may meet new anesthesia doctors. She would very much like to have the same anesthesiologist take care of her when she goes for a procedure. She likes Propofol, it allows for a speedy recovery. Kasey worries about how cystic fibrosis patients absorb and metabolize drugs.

There are 30,000 persons in US with cystic fibrosis with hundreds of mutations in the gene which Kasey has, Delta F 508. Due to better understanding of the disease and advances in medical care, life expectancy for CF patients has increased to 38 years. Kasey said “I am here to express the hurdles faced by Cystic fibrosis patients. I am proud to be involved in raising awareness about CF and raising funds for a cure”. She thanked those involved in CF research and wondered what a cure for CF would mean. She hopes we measure a child’s accomplishments rather than life expectancy and concluded that one day CF will stand for Cure Found.

The next speaker in this session was Kelsey Tainsh, a triplet. She was a high school champion in rowing, a world champion athlete, 3rd in the world in skate boarding. She has worked in movies and has graduated from college with high honors. Now Kelsey travels the country as a motivational speaker. She made us (an audience filled with distinguished professors and many famous pediatric anesthesiologists) stand up and give a high five to our neighbor and say “I am very happy to be here today!”

Kelsey’s story is different from Kasey. She was diagnosed with a brain tumor at age 5, for which she underwent surgery and radiation and had 10 years of normal MRI, a near normal life, filled with school, friends and birthdays. Unfortunately the tumor recurred at age 15, leaving her with a residual stroke. She was obviously devastated not only physically but emotionally as well. She says she lost her friends at school because she was different. Kelsey would hide her paralysed hand in her pocket so people would not notice her disability.

It took her six years to realize that she should accept that she is different, and she realized that people should accept her different look. She told herself that she needed to learn to change her approach of doing things, think outside the box. She had to see life differently, have a different mental and physical aspect of her medical condition. She decided that she was going to fight this and walk again. She went from being in a wheel chair to walker, to a cane and now she walks with a limp but without support! She stated that pediatric anesthesiologists helped her, showed her different ways to do things.

Two years after her stroke, Kelsey wrote a poem called “Aquarium”, which she recited. Kelsey does not like watching fish, she compares being paralyzed by her stroke to being a fish in a tank. People look at a fish in a tank and the fish is trapped, it goes round and round but cannot go anywhere.

Kelsey has had many experiences in the hospital, and she feels that the treatment and care she received from pediatric anesthesiologists is different from other pediatric specialities, they make the experience of being in hospital better. Kelsey did not want her long beautiful hair shaved and she was happy when she woke up because 98% of her hair was still there. Pediatric anesthesiologists did such an amazing job, they all cared. They made her feel safe, as though she was part of their family. In a way she is, her father is a pediatric anesthesiologist! She never had a fear of waking up during and after surgery, because she was being treated by the best doctors. Pediatric anesthesiologist’s not only gave her valuable care and support, but also tools to succeed in her recovery, mentally and physically.

Needless to say, there was a standing ovation for both speakers. For me personally, I felt that these young, brave women put my own physical pain and disability into a fresh perspective. Their stories and points of view give us valuable insight from a patient’s perspective. We as a group of practitioners can improve upon things we can do or not do to help a patient’s peri-operative experience improve.

Dr. Tracy Harrison (Mayo Clinic), the third speaker did a great job with a difficult topic especially since Kasey and Kelsey were a hard act to follow. She had three case presentations on pediatric patients with chronic pain. This review highlights approaches unique to the pediatric patient.

The goals of the session were to characterize the impact of chronic pain in the perioperative period, discuss strategies for acute pain management in the context of chronic pain and chronic pain rehabilitation.

Psychosocial issues are important in pediatric pain with reference to school attendance, delay in development and functional milestones, enmeshed parents, mood disturbances, anxiety, panic or PTSD. In pre anesthetic management- consider oral premed, midazolam, acetaminophen and perhaps gabapentin for extensive procedures in order to get a head start or neuromodulation of pain.

It is important to allow patients to make age appropriate choices, ask them if they would like parents in the OR. Be aware of medication side effects, such as ketamine causing increase anxiety and nightmares. A multimodal approach to prevention of perioperative pain is ideal including regional anesthesia/analgesia. Intraoperative ketamine is potentially helpful, but pediatric literature is lacking. Use of adjunctive medications such as NSAIDS, ketorolac, lidocaine patch and gabapentin should be considered. Non pharmacologic and bio-behavioral pain management strategies such as distraction and diaphragmatic breathing should be introduced early.

In management of acute on chronic pain it is important to ask about baseline pain and functional limitations. Communication with the child that some pain is normal may help, expectations and advice on activity level should be provided and an opportunity offered to ask questions.

The optimal approach to chronic pain rehabilitation in the pediatric patient is: Encourage school attendance and engagement in life from the beginning. The approach should be, children first and patient second. Empowerment and self-esteem play an all-important role. Introduce non-pharmacologic and bio behavioral pain management strategies early. Finally, team involvement is also important –patient, family, surgeon, and anesthesiologist.

Friday Section III: AAP Session

AAP Robert M. Smith Award Presentation

This year’s Robert M. Smith Award was presented to Raafat Hannallah, MD, Professor of Anesthesiology and Pediatrics at George Washington University Medical Center, Attending Anesthesiologist at Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC, by mentee, friend and colleague of more than thirty years, Susan Verghese, MD.

Dr. Connie Houck with AAP Robert M. Smith Award winner Dr. Raafat Hannallah.

Dr. Verghese gave a “gentle roast”, in which she not only described the numerous professional achievements of the “fast and fearless anesthesiologist”, but also introduced Dr. Hannallah, the “Mensch”- the thinker, philosopher, poet, unstoppable dancer and gourmet chef - to the public.

AAP Advocacy Lecture Adolescence 101: Physical and Emotional Development

Barbara K. Snyder MD, FAAP; Chair of the AAP Section on Adolescent Health –

Reviewed by Agnes Hunyady, MD

Seattle Children’s Hospital

Dr. Snyder’s excellent overview of the physical and emotional development of adolescence provided an important introduction to many later topics of the conference on health problems primarily affecting teenagers.

Adolescence is the period between the onset of sexual maturation (puberty) and the attainment of adult societal responsibilities. The tasks of adolescence are complete when a mature self and sexual identity is achieved and the individual has gained independence. It requires a series of dramatic biological, psychological, emotional, cognitive and social changes and the interaction between those domains.

Normal pubertal neuroendocrine changes are characterized by the synchrony and complex interactions of several hormonal axes: increased pituitary growth hormone secretion, adrenal hormone production leading to adrenarche, and the onset of pulsatile hypothalamic GnRH secretion; the hallmark of pubertal initiation that leads to gonadal steroid production through pituitary stimulation. The exact trigger is still unknown, and mechanisms responsible for the wide range in time of pubertal onset are poorly understood. Between the late 1800s and the middle of the last century, both female and male pubertal onset have shifted towards younger ages. Whether the secular trend continues is controversial, but the definition of what is normal has definitely changed: now the lowest “normal” age of thelarche is 7 years and of the male gonadarche is 9 years. Once initiated, appearance of biological pubertal manifestations follows a relatively fixed sequence, and a fairly predictable course, described by the Tanner stages. Current normal age of menarche ranges from 9 to 15 years of age, with a median of 12-12.5 years (depending on ethnicity), followed by regular ovulatory cycles 1-2 years later. Male potential fertility is reached by the age of 13-14.

The dramatic biological changes of puberty that lead to the development of secondary sexual characteristics are accompanied by complex cerebral maturational processes that manifest in morphological and functional changes effecting the volume of grey matter in relationship to white matter, structural connectivity and neurotransmission. Some of these explosive changes during teen years are clearly driven by pubertal hormonal changes, while others appear to be fairly linear and continue well beyond puberty. Structures that show the earliest remodeling include cerebellum, limbic system, amygdala and nucleus accumbens, and appear to be most influenced by pubertal hormones. The above subcortical structures are known to be mostly responsible for affective functions: motivation, drive, emotion, appetite, arousal and reward seeking (thrill seeking, risk taking) behavior. The prefrontal cortex, on the other hand, known to be responsible for reasoning, logic and self-regulation, including regulation of emotions and drives, judgment and planning ahead, continues to mature slowly, long after puberty is over, into the mid-twenties.

Emerging evidence from behavioral studies suggest that such dyssynchrony of maturational processes could perhaps explain why normal adolescent brain development leads to certain common behavioral characteristics, like difficulties in controlling emotions, a preference for physical activity, high reward/ low effort activities and risk taking behavior that is coupled with poor planning. While this period of uninhibited high drive, predilection for experimentation and exploration during the time of independence- seeking gives rise to unparalleled creativity, and makes sense from an evolutionary standpoint, it also creates a period of vulnerability, especially when it occurs in the wrong social context.

Many of the health and social problems of adolescence - substance use/abuse, unsafe sex, resulting in unplanned pregnancies or sexually transmitted diseases - are a consequence of risk behavior. The onset of many mental disorders coincides with adolescence and young adulthood, and are often comorbid with each other and with risk behaviors. Statistics on the prevalence of substance use among teenagers is staggering. Substance use is a risk factors for depression, suicide and violent behavior. This latter manifests as injuries, dating violence, bullying in physical, verbal or psychological form. The prevalence of nutritional problems, including obesity and various forms of eating disorders increased over the past century.

The mortality rate associated with anorexia nervosa, for example, is higher than the rate of all causes of death for adolescent females. While child mortality is generally declining, death rate for 15-24 year olds has been fairly constant, and is due to theoretically preventable causes: unintentional injury (motor vehicle accidents), suicide and homicide.

The role of care givers – parents, teachers, health care providers – during this vulnerable period of adolescence is to find the right balance of monitoring and support while preserving autonomy. Privacy is of utmost importance for teens, especially when it comes to sensitive history (mood, body image, sexual behavior, substance use). While the age of majority is 18 years, in almost all states, health care can be provided to patients younger than 18 year olds without parental consent in medical or psychiatric emergency situations, in issues related sexual behavior (obstetric care, pregnancy prevention, treatment and prevention of sexually transmitted diseases, in some states abortion), and in substance abuse issues.

Friday Session IV: Trouble with the Curve

Reviewed by Chris Glover, MD

Texas Children's Hospital

Houston, TX

This review covers the Friday afternoon session titled Trouble with the Curve…..sadly for all of us in attendance who are Justin Timberlake fans this dealt not with Clint Eastwood or baseball but with scoliosis management.

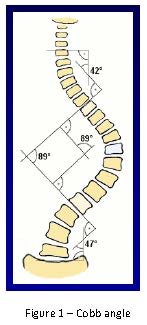

Dr. Mary Ellen McCann (Children’s Hospital, Boston) started the session giving a synopsis of scoliosis and the methods of monitoring spinal cord integrity during repair. Scoliosis is a defined as a deformity of the thoracolumbar spine seen in up to 4% of the population. The degree of scoliosis is quantified by the Cobb angle, which is measured by the intersection of perpendicular lines extending from lines along the vertebral body at the superior and inferior margins of the spine deformity (Fig. 1). Surgical repair is usually undertaken once the Cobb angle is greater than 50 degrees.

Scoliosis can be categorized as idiopathic, congenital, or neuromuscular. Idiopathic scoliosis comprises 70-80% of total cases. Nonidiopathic scoliosis can include neuromuscular scoliosis, congenital scoliosis, those status post prior thoracic surgery and trauma. Given risks associated with correction which can lead to devastating neurologic injury; the use of intraoperative monitoring is to prevent neurologic injury.

With regards to the evidence behind neurophysiologic monitoring, Dr. McCann pointed towards a meta-analysis by Fehlings that evaluated efficacy of neuromonitoring in 32 articles over 20 years. Findings from this review were high level for use of motor evoked potential (MEP) monitoring as they are both sensitive and specific in detecting neurologic impairment. There is also high-level evidence that MEPs are better in assessment of neurologic function when compared to somatosensory evoked potential monitoring. This is countered with low to very low level evidence that intraoperative monitoring in any form reduces rates of new neurologic deficits or that intraoperative responses to neurologic alerts reduces rates of neurologic deterioration [1].

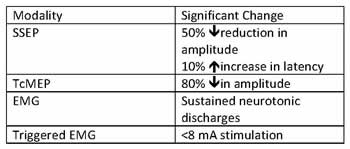

Dr. McCann provided an overview of each of the individual testing modalities noted. Significant changes associated with each monitoring modality are listed in Table 3.

Somatosensory evoked potential (SSEP) monitoring records signals from the sensory cortex after stimulation in the periphery at sites such as the median/ulnar/ post tibial (usually post tib) where meaningful change is noted as a conduction latency >10% and decrease in amplitude by 50%. SSEP’s correlate with function of the dorsal column and perfusion to the posterior cord by the paired posterior spinal arteries. Limitations associated with this technique are that motor pathways are more sensitive with regards to ischemic change and recordings noted must be averaged over 5 minutes. Advantages mentioned in the lecture include SSEP use in the very young (3months) as well as the ability to use nondepolarizing muscle relaxants.

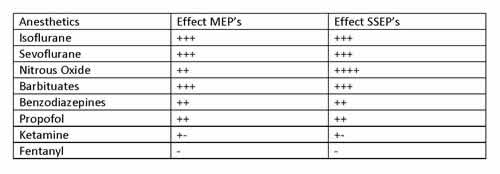

Transcranial stimulation for motor evoked potentials (TcMEPs) can occur via single or multiple stimulus technique and occurs by cortical stimulation with evoked potential recording in the peripheral structures. This modality covers the lateral corticospinal tract, but is used as an overall assessment on anterior cord perfusion. Application of strong electrical impulses across the cranium generates 2 waveforms: a D (direct) wave and an I (indirect) wave form. D waves are unaffected by anesthesia and signifies the depolarization of an axon which correlates to postoperative motor function. But as electrodes need to be placed epidurally this monitoring modality is not commonly used. I waves are quite sensitive to anesthetics and quite hard to reliably produce which led to the development of multiple stimulus TcMEPs where electrical stimuli are repetitively administered to the cortex and EMG needles are place in the extremities to record compound muscle action potentials (cMAP). The use of TcMEPs can be problematic in young children given immaturity of cranial sutures and the relative immaturity of motor pathways. Other limitations for this technique lie in comorbid patient conditions, which can include hydrocephalus, cerebral palsy, seizure disorder, peripheral neuropathy or myopathy. Safety concerns are also associated with TcMEP as tongue injury and seizure activity has been reported in the literature [2]. With regards to anesthetic agent effects on evoked potential monitoring, the information seems best served in the table below (Table 1).

Table 1. Anesthetic Agent Effects on TcMEP/SSEP

A general rule of thumb with use of volatile anesthetics in cases where intraoperative monitoring is planned is conservative use to less than 0.5 MAC although Dr. McCann pointed to a study that reported reproducible signals in 9/10 patients receiving 0.6 MAC with 50% N2O although significantly decreased amplitude was noted [3]. Propofol seems to provide a superior environment for monitoring purposes with dosing not to exceed 200 mcg/kg/min. Ketamine was also discussed with the lecture’s main focus on dysphoria occurring in 14% of patients when low dose ketamine was combined with low dose propofol [4]. Optimal management goals during scoliosis repair includes MAP >65-70 mm Hg, normothermia, normovolemia, Hct >21%, and normal cardiac output.

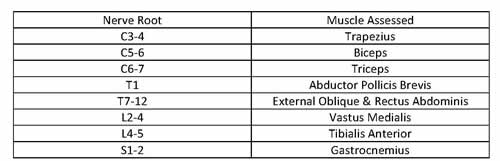

Electromyography (EMG) allows for assessment of potential nerve injury by electrical stimulation along the pedicle track or screw with placement of recording needle electrodes in specific muscles innervated by nerve roots (see Table 2). A normal EMG has low amplitude, high frequency activity. EMG can be classified as free running or triggered EMG. Free running EMG looks for neurotonic discharges, which imply trauma to roots or peripheral nerves. Stimulus triggered EMGs are used for assessment of pedicle screw sites as perforation of a pedicle results in lowered impedance and local nerve root activation at lower stimulus intensity. Advantages for the use of stimulus triggered EMG is that each pedicle crew can be tested individually during scoliosis repair.

Table 2. EMG Dermatomes and Associated Muscles.

Dr. McCann then discussed the Stagnara wakeup test, which remains the gold standard for neurologic assessment, although it is limited via its lack of continuity. This test requires a tailored anesthetic that allows the patient to emerge in the operating room and follow specific commands such as move your hands and feet. Multiple providers should be available with 1 preferentially at the head and the other at the lower extremities for assessment during emergence. A preoperative consultation is imperative to decrease anxiety, to inform the patient and family on the details of the “wake up” process and to answer questions related to emergence, pain, and recall. Risks for this modality deals with potential for extubation, movement off the table with inherent issues of dislodgement of lines or implants, and air embolus.

Table 3. Intraoperative Monitoring and Associated Significant Change.

The strategies for changes in neurologic status during operative repair include:

- Maximizing perfusion via increasing the BP, Hct, and temperature.

- Assessing reversal of last intraoperative maneuver.

- Consideration of removal of all corrections and implants.

Although the information covered was quite extensive, the benefits cited by Dr. McCann at the end of her talk centered on the inadvertent improvement in communication amongst services when intraoperative monitoring is used along with the expected benefits of an early warning system in detecting changes in neurologic monitoring.

Dr. Bishr Haydar (CS Mott Children’s Hospital) covered blood conservation in the second portion of this session. This important topic is based on estimates of blood loss approaching 200 cc/level repaired over the first 24 hours as well as the potential for dilutional and consumptive coagulopathy that exists in these patients [5, 6].

Relevant risk factors for increased potential blood loss include:

- Neuromuscular versus idiopathic scoliosis.

- Multiple level repair.

- Weight < 30 kg.

- Duration of surgery.

Dr. Haydar discussed potential complications with transfusion and reasons for limiting exposure in this patient cohort. This includes blood borne infections, transfusion reactions, and potential issues with delayed wound healing. There also seems to be an association with Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in those exposed to blood for this procedure.

Dr. Haydar eloquently divided the process of blood conservation into 2 phases of care: the preoperative period and the intraoperative period. A checklist during the preoperative period entails an evaluation for potential anemia and most importantly a history and physical. An interesting point during this discussion centered on the efficacy of erythropoietin as it decreased transfusion requirements in one retrospective analysis. But a following prospective trial yielded no such benefit, which was doubly concerning given the associated cost [7].

Intraoperative factors associated with decreasing the potential for blood loss starts not surprisingly before incision. Appropriate positioning results not only in a reduction of estimated blood loss by 50%, but also a decrease in abdominal pressure which translates into a 1/3 potential decrease in the IVC pressure [8, 9]. Autologous donation was reported to reduce the need for donor units with a cost less than the use of cell salvage [10].

Hypothermia is something that should be avoided at all costs given that prolongation of the PT/PTT/INR occurs below 35°C. When profound hypothermia is present expect the coagulopathy to be irreversible until temperature correction is attained. The anesthetic technique has impact on estimated blood loss and multiple articles cited use of intrathecal morphine (IT) in mitigating blood loss during scoliosis repair [11]

Antifibrinolytics were also discussed. A recent meta-analysis points to a decrease in overall bleeding when antifibrinolytics (i.e. aminocaproic acid and tranexamic acid) are used but transfusions occurred at similar rates in populations who receive or did not receive these agents [12]. Transfusion guidelines were mentioned with absolute indications occurring with a Hgb < 6 g/dl. Relative indications include potential for ongoing loss (as all scoliosis cases are), low volume status, low cardiopulmonary reserve, and high oxygen consumption.

In summary, Dr. Haydar discussed the importance of starting blood conservation before day of surgery with emphasis placed in the preoperative phase of care. Intraoperative measures to follow are proper positioning, normothermia, and consideration of IT morphine. Although the evidence is equivocal, antifibrinolytics and cell salvage seem to play a role in blood conservation as part of a larger strategy to decrease blood loss for these complex patients.

Dr. Patrick Ross (Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles) finished the discussion by discussing analgesic options for use in the postoperative care of scoliosis cases.

Discussion initially centered on use of intrathecal opioids, which was cited in previous lectures in this session. Lower dosing regimens seem better tolerated as higher IT morphine resulted in increased respiratory depression with minimal improvement in pain scores or time to rescue [13]. The blood loss benefit starts at doses as low as 5 mcg/kg and Dr. Ross noted pain scores consistently reported lower in those with intrathecal morphine dosing in the range of 3-7 mcg/kg [11]. While epidurals provide better analgesia the failure rate reported in the presentation (up to 37%) may present challenges for those who do not perform epidurals with regularity. With regards to comparisons between forms of postoperative pain control the data seem equivocal with all pointing to low scores on pain evaluation. Generally speaking the data trends towards epidurals being more efficacious than PCA and IT morphine resulting in further benefit to the modalities listed [14-16].

Bupivacaine was discussed briefly and while it use results in decreased postoperative opioid use; the potential risk associated with increased infection has limited its overall utilization in practice [17]. Remifentanil hyperalgesia was briefly discussed with conflicting data on ketamine’s ability to prevent this phenomenon. When looked at via a meta-analysis ketamine provides lower PACU pain scores, but did not decrease postop opioid use [18].

Data presented on IV acetaminophen in pediatrics not surprisingly for purveyors of multimodal analgesia revealed improved analgesia but no change in overall opioid usage. In adults morphine usage actually decreased by 46% in the study cited [19, 20] Nonsteroidals, such as ketorolac also pointed to decreased pain scores and morphine usage. With regards to its safety profile Dr. Ross pointed to studies that respectively presented no additional risk associated with ketorolac usage in the incidence of transfusion, reoperation, or risk of reoperation [21-23].

Methadone has shown some efficacy in adult studies, but efficacy trials in pediatric spine surgery revealed no change in opioid use or pain scores. Gabapentin resulted in decreased pain scores and morphine usage; but did not decrease opioid related side effects.

The second half of Dr. Ross’ talk centered on the CHLA protocol for which I will refer readers to the lecture slides. The overarching message discussing multimodal therapy in this session was that while each addition likely lowers pain scores and opioid use there remains an inability to separate effect of the individual from the group.

Bibliography

- Fehlings, M.G., et al., The evidence for intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring in spine surgery: does it make a difference? Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2010. 35(9 Suppl): p. S37-46.

- Legatt, A.D., Ellen R. Grass Lecture: Motor evoked potential monitoring. Am J Electroneurodiagnostic Technol, 2004. 44(4): p. 223-43.

- Ubags, L.H., C.J. Kalkman, and H.D. Been, Influence of isoflurane on myogenic motor evoked potentials to single and multiple transcranial stimuli during nitrous oxide/opioid anesthesia. Neurosurgery, 1998. 43(1): p. 90-4; discussion 94-5.

- Kawaguchi, M., et al., Low dose propofol as a supplement to ketamine-based anesthesia during intraoperative monitoring of motor-evoked potentials. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2000. 25(8): p. 974-9.

- Gibson, P.R., Anaesthesia for correction of scoliosis in children. Anaesth Intensive Care, 2004. 32(4): p. 548-59.

- Vitale, M.G., et al., Quantifying risk of transfusion in children undergoing spine surgery. Spine J, 2002. 2(3): p. 166-72.

- Vitale, M.G., et al., Efficacy of preoperative erythropoietin administration in pediatric neuromuscular scoliosis patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2007. 32(24): p. 2662-7.

- Park, C.K., The effect of patient positioning on intraabdominal pressure and blood loss in spinal surgery. Anesth Analg, 2000. 91(3): p. 552-7.

- Lee, T.C., L.C. Yang, and H.J. Chen, Effect of patient position and hypotensive anesthesia on inferior vena caval pressure. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 1998. 23(8): p. 941-7; discussion 947-8.

- Elgafy, H., et al., Blood loss in major spine surgery: are there effective measures to decrease massive hemorrhage in major spine fusion surgery? Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2010. 35(9 Suppl): p. S47-56.

- Gall, O., et al., Analgesic effect of low-dose intrathecal morphine after spinal fusion in children. Anesthesiology, 2001. 94(3): p. 447-52.

- Basta, M.N., P.A. Stricker, and J.A. Taylor, A systematic review of the use of antifibrinolytic agents in pediatric surgery and implications for craniofacial use. Pediatr Surg Int, 2012. 28(11): p. 1059-69.

- Eschertzhuber, S., et al., Comparison of high- and low-dose intrathecal morphine for spinal fusion in children. Br J Anaesth, 2008. 100(4): p. 538-43.

- Milbrandt, T.A., et al., A comparison of three methods of pain control for posterior spinal fusions in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2009. 34(14): p. 1499-503.

- Gauger, V.T., et al., Epidural analgesia compared with intravenous analgesia after pediatric posterior spinal fusion. J Pediatr Orthop, 2009. 29(6): p. 588-93.

- Ravish, M., et al., Pain management in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis undergoing posterior spinal fusion: combined intrathecal morphine and continuous epidural versus PCA. J Pediatr Orthop, 2012. 32(8): p. 799-804.

- Ross, P.A., et al., Continuous infusion of bupivacaine reduces postoperative morphine use in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis after posterior spine fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2011. 36(18): p. 1478-83.

- Dahmani, S., et al., Ketamine for perioperative pain management in children: a meta-analysis of published studies. Paediatr Anaesth, 2011. 21(6): p. 636-52.

- Hiller, A., et al., Acetaminophen improves analgesia but does not reduce opioid requirement after major spine surgery in children and adolescents. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2012. 37(20): p. E1225-31.

- Hernandez-Palazon, J., et al., Intravenous administration of propacetamol reduces morphine consumption after spinal fusion surgery. Anesth Analg, 2001. 92(6): p. 1473-6.

- Pradhan, B.B., et al., Ketorolac and spinal fusion: does the perioperative use of ketorolac really inhibit spinal fusion? Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2008. 33(19): p. 2079-82.

- Sucato, D.J., et al., Postoperative ketorolac does not predispose to pseudoarthrosis following posterior spinal fusion and instrumentation for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2008. 33(10): p. 1119-24.

- Vitale, M.G., et al., Use of ketorolac tromethamine in children undergoing scoliosis surgery. an analysis of complications. Spine J, 2003. 3(1): p. 55-62.

Friday Session V: Refresher Courses

Reviewed by Cheryl K. Gooden, MD

Mount Sinai Medical Center

New York, NY

The first speaker in the refresher course session, Dr. Jennifer Lee (The Johns Hopkins Hospital) presented “Resuscitation Science Update.” She focused on the most recent updates in Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) guidelines, the scientific rationale behind the most recent updates, and the special adaptations of PALS to the perioperative setting.

Dr. Lee highlighted the fact that the risk of cardiac arrest was greatest among the neonate and infant population undergoing either non-cardiac or cardiac surgeries. Neonates, infants and children undergoing cardiac surgery were also considered at greater risk of cardiac arrest when compared to those undergoing non-cardiac surgery. Probably, the best source of information regarding the etiology of cardiac arrest can be obtained from the Pediatric Perioperative Cardiac Arrest (POCA) Registry. As noted, the most common causes of cardiac arrest include cardiovascular, medication, respiratory and equipment.

In 2010, with the roll-out of the updated PALS guidelines was a major change from A-B-C to C-A-B, by the American Heart Association. These changes were the results of evidence-based findings. For the most part, compressions should be started immediately. The “take away” message with regards to optimal chest compressions is:

- Compression rate - at least 100/min,

- Compression depth - at least 1/3 AP diameter about 2 inches (5 cm),

- Chest wall recoil - allow complete recoil between compressions, rotate compressors every 2 minutes,

- Compression interruptions - minimize interruptions in chest compressions; attempt to limit interruptions to < 10 seconds.

Dr. Lee concluded her presentation with the clinical adverse events of venous air embolism, hyperkalemic arrest, local anesthetic toxicity, and anaphylaxis. In addition, she outlined the management for each of these adverse events.

A recommended reference on the topic of PALS in the perioperative setting:

Shaffner D, Heitmiller E, Deshpande J. Pediatric perioperative life support. Anesth Analg 2013;117:960-979.

The speaker for the second half of the refresher course session, Herodotos Ellinas, MD (Medical College of Wisconsin) presented “Disclosure of Adverse Events.” He focused on clinical cases where disclosure was utilized, communication strategies for effective disclosure, barriers to disclosure, and resources to assist with the disclosure of adverse events.

Dr. Ellinas provided interesting historical and current perspective on patient safety issues. He stated that by 1985, the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation took the position that “no patient shall be harmed by the effects of anesthesia.” In 2006, the National Quality Forum implemented disclosure as one of the endorsed safe practices. He noted the need for improvement to reduce the incidence of medical error.

Along these same lines, Dr. Ellinas highlighted the results of a survey of 687 anesthesiologists that demonstrated, 85% of them had experienced at least one drug error or “near miss.” (Can J Anaesth 2001;48:139-146)

The reporting of an adverse event or error may be multi-level within an institution as well as outside agencies. There are benefits of disclosure. For the most part it will serve to answer questions. In the process of answering questions, the disclosure may help to diffuse anger when present.

Dr. Ellinas provided suggestions of “what not to say,” and include 1) Do Not speculate about what happened, 2) Do Not blame others, and 3) Do Not accept fault unnecessarily based on emotions. He emphasized that when meeting with the patient and family,

- Be honest, calm, concerned, direct

- Sit down, make eye contact

- Keep it simple

- Ask for questions or concerns

Dr. Ellinas concluded by offering several resources that may be quite useful when it is necessary to respond to an adverse event. Some of these resources include:

National Quality Forum

http://www.qualityforum.org/about/

The Sorry Works! Coalition

http://www.sorryworks.net

Saturday Session I: A Clear and Present Danger

Reviewed by Katherine R. Gentry, MD

Seattle Children's Hospital

Seattle, WA

Saturday morning brought an eye-opening set of lectures on drug abuse and diversion. Moderated by Dr. Jeffrey Galinkin (Children’s Colorado), this session featured three speakers who impressed upon us the prevalence of drug abuse in our country (particularly among adolescents), interactions between illicit drugs and anesthetic agents, and the incidence of drug diversion and abuse among anesthesiology residents.

The first panel speaker was Dr. Wilson Compton, Deputy Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, with a talk entitled “Adolescent drug abuse: risks for development.” Dr. Compton’s main themes were the prevalence of drug abuse in adolescents and the science of addiction.

So how common is drug abuse? For comprehensive data to answer this question, check out: http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/.

Some key numbers from the 2013 survey of past-year use in 12th graders are as follows:

- 62% have used alcohol

- 36% have used marijuana

- 8.7% have used amphetamines (non-medical use)

- 7.4% have used Adderall (non-medical use)

- 5.3% have used Vicodin (non-medical use)

- 3.6% have used Oxycontin (non-medical use)

- 0.6% have used heroin

Marijuana use is increasing, while alcohol use is on the decline. Of particular note was that 6-7% of 12th graders report daily use of marijuana. What are the risks of marijuana use? A two-fold increased risk of auto accidents, an association with mood disorders, lack of motivation and addiction. What is the risk of becoming dependent on marijuana? About 9%. In comparison, 32% of nicotine users and 23% of heroin users become dependent on these drugs.

Dr. Compton also discussed prescription drug abuse. There has been a 3-fold increase in the number of opioids prescribed from 1991-2011 (with the 2011 total of 219 million prescriptions). The majority of prescription opioids are not bought on the street. Fifty-five percent of analgesic addicts reported getting their drugs free from a friend or relative, and another 16% bought/took them from a friend/relative. It also appears that “doctor shopping” is not necessary for addicts to get an adequate supply of opiates. Of the friends/relatives who gave away their prescription drugs for free, 79% of them got their prescriptions from a single doctor. Another striking statistic: the rate of death from drug overdose has now surpassed that from motor vehicle crashes (>15,000/year).

There was not enough time for Dr. Compton to cover all of his slides on the science of addiction. At the risk of oversimplifying, the major point was that addictions are developmental brain diseases. How is drug addiction a developmental problem? The risk of becoming addicted is highest in persons who begin using drugs in their late teens. Environmental factors and social stressors are also implicated in the development of addiction behavior.

The second speaker was Dr. David Birnbach (University of Miami), with a talk entitled “Anesthetic Interactions with Abused Substances.” The pervasiveness of drug abuse was highlighted through headlines from the lay press and case reports from the medical literature. Dr. Birnbach offered recommendations for the management of illicit drug-anesthetic interactions.

Of the numerous examples of drug abuse presented in this session, the most disturbing to me was the description of “pill parties.” Kids bring pill bottles from home, pour them into a big bowl, and then take turns ingesting the mystery pills. Imagine the dangerous and surprising combination of symptoms that might result from such ingestion.

Dr. Birnbach gave particular attention to manifestations of cocaine use in the perioperative setting. Dysrhythmias, MI, convulsions, and drug interactions can be seen. The clinical picture is often confusing, as symptoms of cocaine intoxication (tachycardia, hypertension, convulsions, hyperreflexia, tremors, acidosis, emotional lability, and dilated pupils) mimic other conditions such as preeclampsia, pheochromocytoma, and thyroid storm. Even more worrisome is that cocaine use is significantly under-reported or denied. In one study, when patients were unaware that they were being tested for drugs, 60% testing positive for cocaine denied it. One-fifth to one-third of trauma patients may test positive for cocaine. The management of an intraoperative crisis involving cocaine is somewhat controversial. Dr.Birnback offered the following suggestions: for arrhythmias, give calcium channel blockers; for convulsions, give benzodiazepines; for angina + EKG changes, give nitroglycerin. The anesthetic agents/adjuncts to avoid in the presence of cocaine include halothane, ketamine, succinylcholine, and beta blockers.

A brief review of the anesthetic implications of opioid and marijuana abuse followed. Opiate intoxication can lead to hypothermia and respiratory failure due to hypoventilation, aspiration and non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema. In the opioid addicted patient, opioid therapy should be continued so as to not precipitate withdrawal. If withdrawal signs are suspected, treat with clonidine. Physical effects of marijuana can include tachycardia, myocardial depression, supraventricular or ventricular ectopy, upper airway irritability, and bronchospasm.

The third session was particularly sobering: “Drug Diversion and the Anesthesiologist” by Dr. Keith Berge (Mayo Clinic). He provided convincing evidence that anesthesiology is a rather dangerous career choice. For anesthesiologists with a substance abuse problem, relapse rates are high and people tend to die when they relapse.

The third session was particularly sobering: “Drug Diversion and the Anesthesiologist” by Dr. Keith Berge (Mayo Clinic). He provided convincing evidence that anesthesiology is a rather dangerous career choice. For anesthesiologists with a substance abuse problem, relapse rates are high and people tend to die when they relapse.

Dr. Berge presented the findings of a study he and other colleagues published in JAMA (2013) that was aimed at determining the incidence and outcomes of substance use disorders in all anesthesia residents in the U.S. between 1975-2009 (1). Of the 45,581 people who entered a residency, 1,042 had a substance use disorder (SUD) “flag,” and confirmatory evidence was found in 842 residents. Of those, 120 died in residency. 512 developed a SUD subsequent to training and 384 developed it during training.

Of those developing SUD in residency, the median time from starting residency to first use was 30 months. First use to detection was about 4 months. The overall incidence was 2.2 per 1000 resident-years, with a vast male predominance. In terms of relapse, of the 310 residents detected to have SUD who survived, 29% relapsed at least once, and the median time to relapse was 2.6 years.

Mortality rates due to SUD are notable. Of the residents with an identified SUD, 11% have died with the cause of death is associated with substance use. Occupations associated with a higher death rate are farming, fishing, and forestry, with a mortality rate of 21.2 per 100,000. Anesthesia residency has a mortality rate of 15.7 per 100,000. Interestingly, in this study, death and relapse rates were not much different across substances, and oral opioids were associated with a higher death rate than IV opioids.

These sessions served as a reminder that drug use remains a serious problem in our society. We cannot deceive ourselves into thinking that as pediatric providers we will be spared the challenges of caring for patients who abuse substances. In addition, substance among anesthesia residents and providers is a serious problem with deadly consequences. We must remain vigilant not only over our patients but within our work environment to prevent and address drug diversion.

For more resources on drug abuse, screening, and education materials, go to www.drugabuse.gov. Search “NIDAMED” for screening tools.

Warner DO, Berge K, Sun H, Harman A, Hanson A, Schroeder DR. Substance use disorder among anesthesiology residents, 1975-2009. JAMA 2013;310:2289-96.

Saturday Session II: Poster Presentations and Awards

Reviewed by Jorge A. Galvez, MD

Children's Hospital of Philadelphia

Philadelphia, PA

The Society for Pediatric Anesthesia was moderated by Joseph D. Tobias and Genie Heitmiller. Five posters were selected for oral presentations from a total of 346 posters that were displayed throughout the conference. The oral presentations were:

American Academy of Pediatrics Research Awards:

First Place:

“Normalization of Fractional Anisotropy and Apparent Diffusion Coefficient Values Facilitate Appropriate Comparison of Corpus Callosum Microstructural Changes in the Developing Newborn.”

Authors: Nathaniel Greene, Andrew Emerald, Blaine Easley, Ken Brady, Jill Hunter, Elisabeth Wide, Dean Andropolous.

Institution: Texas Children’s Hospital, Baylor College of Medicine.Second Place:

“High body mass index in older children as a risk factor for peri-operative complications”

My Liu, Olubukola Nafiu.

Institution: C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, University of Michigan.Third Place:

“Present-day American children have outgrown common age-based weight estimation formulae”

Authors: Mike Y. Wang, Olubukola Nafiu

Institution: C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, University of Michigan

Society for Pediatric Anesthesia Young Investigator Awards:

First Place:

“Pediatric Postoperative Pain and Genome-wide Association Study (GWAS): Novel Fatty Acid Amide Hydrolase Genetic Variants Predict Postoperative Opioid-Induced Respiratory Depression, PONV and Length of Hospital Stay.

Authors: Jagroop Mavi, Vidya Chidambaran, Hope Esslinger, Xue Zhang, Lisa Martin, Senthilkumar Sadhasivam.

Institution: Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, University of Cincinnati.Second Place:

“Anesthetic Agents Induce Protein Misfolding and Affect Carbon Dioxide Response in the Brainstem”

Authors: Matthew Coghlan, Sadiq Shaik, Jason Maynes.

Institution: The Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto.

Following the oral presentations, the audience proceeded to a guided walk-around session for oral poster presentations organized by subspecialties. Each session was moderated by an expert in the field, including Drs. Shobha Malviya, Helen Lee, Jennfer Lee-Summers, Richard Levy, Wanda Miller-Hance, Philip Morgan, Olubukola Nafiu, Olutoyin Olutoye, Senthil Sadhasivam, Susan Verghese, Terri Voepel-Lewis, and Mehernoor Watcha.

The SPA meeting continues to organize electronic poster presentations that allow for a unique scientific discussion. Each poster viewing area consisted of a large monitor where the posters were displayed in sequential order. The presenters load their poster at the appointed time and guide the viewers through their poster in an interactive discussion. The group is able to stay in one area while the posters are presented.

Saturday Session III: AAP Ask the Experts Panel

Reviewed by Toyin Olutoye, MD

Texas Children’s Hospital

Houston, TX

Speakers: Dr. Jamie McElrath Schwartz (National Children’s Hospital, Washington, DC) and Dr. Thomas Taghon (Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio)

Dr Jamie McElrath Schwartz (National Children’s Hospital, Washington, DC) stated that The Joint Commission has made transfer of care and handoffs an important safety goal. Dr. Jeffrey Cooper, founder of the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation (APSF), identified this issue when he conducted a survey (1975 to 1980) and found that 97% of critical incidents were associated with periods of relief of patient care between anesthesiologists. He recommended a standardized approach to handoffs.

More recent survey data (2004) revealed only 10% of institutions had a standardized approach to handoffs.

In 2010, the SPA Quality and Safety Committee, comprising faculty from multiple institutions, developed a hand off tool which was assessed in a pilot study and subsequent evaluation. This study, performed in six institutions over six months, examined the following endpoints: time, ability to detect useful missing information and usefulness of the tool using a Likert scale. Approximately 64% of evaluators felt that important information was detected using the structured handoff tool. Despite this finding, the overall conclusion was that while use of a standardized handoff tool was feasible and important information could be detected with its use, evaluators were unclear as to the usefulness, based on the Likert scale results obtained in the study.

Dr. Schwartz discussed that physicians tend not to like checklists and this was attributed to cultural bias against standardization, subtle snobbery of “medicine as an art”, the intense amount of information involved in the use of a checklist in contrast to the promptness by which critical information may be communicated during initial transfer of care or handoff. She alluded to the fact that by using a checklist, the most critical patient information may be lost by the time the checklist is followed in its entirety.

Nevertheless, she concluded that while handoffs are generally unstructured, they are critical to the anesthetic management of patients, should include microcosm and macrocosm of information and should include checklists.

Dr. Thomas Taghon (Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio) emphasized the findings of Ong & Coiera (2011) in a systematic review study looking at failures of handoffs in surgical patients and their recommended improvement strategies which included:

- Standardize handoff procedures and content

- Multidisciplinary team handoffs

- Initiation of a formal handoff procedure with minimal interruptions.

He went on to depict the policy of 5 P’s at Nationwide Children’s hospital, implemented for transfer of patients from operating room to an intensive care unit (PICU, NICU or CTICU) namely:

- Patient

- Past medical history

- Procedure

- Plan

- Problems

- Potential for pitfalls

They identified personnel whose presence was mandatory at the handoff:

- Anesthesiologist

- Anesthesiologist fellow/trainee

Surgical attending or fellow (particularly fellow that was involved in the surgical procedure) - Intensive care personnel (category of which could vary ,depending on the unit, but the person had to be the most senior person available)

In addition, the information to be conveyed was also standardized in a paper hand off tool. In order to improve compliance information about the handoff tool was included in orientation packets for PICU, NICU and Anesthesiology departments. Subsequent audits revealed that while handoffs were being performed, the checklist was not being utilized on a regular basis, although ICU staff tended to use it more often than not. Cultural barriers to handoff discovered at Nationwide Children’s hospital included: reverse handoff from ICU staff to the anesthesiology team, buy-in from bedside nurses, routine use of the checklist and a standardized routine for hand off processes.

Nevertheless, it was discovered that initiation of the process by the anesthesiologist enabled a quick roundup of the necessary members so the handoff could begin promptly on arrival of the patient to the ICU.

Session IV: Refresher Courses

Reviewed by Douglas R. Thompson, MD

Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine

Seattle Children’s Hospital

University of Washington

Seattle, WA

The Single Ventricle vs. the Laparoscope

In the first lecture Dr. Scott C. Watkins (Vanderbilt University) reviewed the physiology of the single ventricle using hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) as the model. He quickly reviewed physiology of the unpalliated state before moving on to consider the various stages of single ventricle palliation, leaving Fontan physiology as a separate topic not covered in his lecture. Anesthetic considerations were discussed in each stage with the caveat that in his opinion the most important aspect of care in these patients is vigilance and having a rescue plan in place.

Unpalliated: In HLHS in the unpalliated state, systemic blood flow is ductal dependent and requires an atrial level communication for adequate mixing of deoxygenated and oxygenated blood. These patients tend to have a well developed right sided heart and therefore tend to have pulmonary over circulation. With a goal of a balanced pulmonary and systemic circulation, questions to consider then when caring for such patients focus on; the status of the ductus, whether the atrial communication is open or restrictive, if there is adequate systemic perfusion and if the circulation is balanced. Resistance in the systemic circuit at this stage is often fixed by an obstructive lesion which leaves manipulation of the pulmonary system and pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) via PaO2 and PaCO2 to achieve a balanced circulation.

Dr. Watkins cautioned providers to be cognizant of changes in PVR which can occur with intubation; for example pre-oxygenation and hyperventilation, as these will lead to pulmonary over circulation at the expense of systemic perfusion. Furthermore Dr. Watkins advocates placing an arterial line if intubating the patient, or for invasive procedures for close management of blood gas values targeting blood gas values of 7.4/40/40 and following lactates. With regards to management of pulmonary blood flow (PBF) a study was reviewed showing that in the unpalliated state, while both hypercarbia and hypoxia were equally effective in reducing PBF, hypercarbia was associated with improved oxygen delivery, SBP and DBP.

Stage I Palliation: Stage I palliation for HLHS takes one of three forms, a classic Norwood with aortic arch reconstruction and a BT shunt (subclavian to PA), a Norwood with a Sano shunt (RV to PA), or a hybrid procedure consisting of stenting the PDA and banding of the PAs. Dr. Watkins related that in some series the pre-transplant survival is improved in patients with a Sano shunt, (despite requiring more subsequent interventions such as in cath lab procedures), theories for this include more stable hemodynamics in the inter-stage period, specifically higher diastolic blood pressures with improved coronary perfusion.

When approaching the patient after stage I palliation, peri-operative management will center on whether the patient has had a BT shunt or a Sano shunt. As mentioned above, in the patient with a BT shunt, maintenance of DBP is critical. Also in the BT shunt patient PVR has less of an impact given the fixed nature of the shunt whereas in the Sano patient control of PVR can limit the volume load on the ventricle.

Finally, thrombosis of the shunt is more common in the BT shunt patient. With both the BT shunt and Sano shunt, the goal SpO2 will be between 75-85% and focus should be placed on maintaining SVR, MAP and intravascular volume.

Stage II Palliation: Stage II palliation for HLHS consists of cavopulmonary anastomosis (Bidirectional Glenn) with the SVC being connected to the pulmonary artery (PA) and takedown of the BT/Sano shunt. This creates a series circuit and helps unload volume from the ventricle (given the unloading of PBF). In this stage PBF is affected by several factors such as intra-thoracic pressure, venous pressure, acid-base status, and PaCO2. Dr. Watkins reviewed a study showing that increased PaCO2 led to an increase in SaO2 in the Glenn circuit and improved systemic circulation as evidenced by decreased lactate levels.

Anesthetic goals and considerations at this stage include maintenance of adequate intravascular volume, minimizing PVR and promoting PBF. During controlled ventilation, use of low I:E ratios, low RR, normal TV +/- PEEP, and maintaining normal acid base are all prudent. Relative to Stage III (Fontan), decreases in PBF will result in lower saturations but the cardiac output (CO) will be preserved via venous return from the IVC, as opposed to the Fontan patient where a decrease in PBF will result in lowers saturations and lower CO.

Dr. Watkins went on to review commonly encountered non-cardiac surgery procedures in the single ventricle patient. Using data from his institution, these frequently included gastrostomy, fundoplication, PICC, airway endoscopy, and central line placement and most commonly took place between stage I and II palliation, which is a higher risk stage. Review of peri-operative data at his center showed that increased intraoperative instability was associated with procedures done before stage II palliation, more invasive procedures and use of pre-operative ACE-inhibitors.

Specifically when looking at HLHS and feeding/reflux surgery at his institution, there was a high rate of peri-operative instability and escalation of care. Regional anesthesia was associated with increased induction instability and need for inotropic drugs possibly related to the prolonged period of lack of surgical stimulation.

Finally, Dr. Watkins went on to discuss laparoscopic surgery in the setting of the patient with a single ventricle. Pulmonary mechanics are affected in several ways during laparoscopic surgery, with an increase in intra-abdominal pressure causing a decrease in pulmonary compliance with concomitant increase in PIP, decrease in FRC, VC and TV.

A study was reviewed which showed that CO2 adsorption increases with increasing insufflation pressures, insufflation time and younger patients. Dr. Watkins also reviewed a study showing that ETCO2 is NOT an accurate reflection of PaCO2 with factors contributing to the discrepancy including right to left shunting, high PA pressures and increased PBF. Importantly hyperventilation may not be effective in correcting the increased PaCO2.

With regards to cardiovascular mechanics and abdominal insufflation, there is a biphasic response with an initial increase in venous return (VR) leading to increased CO, but this is followed by decreased VR and decreased CO likely due to reduced preload from collapse on the vena cava. SVR increases due to multiple effects including aortic compression, splanchnic vasoconstriction and activation of sympathoadrenal system. Neither is well tolerated in the patient with single ventricle physiology.

Dr. Watkins concluded the lecture with a summary of considerations for the patient after stage I and stage II palliation requiring a laparoscopic procedure. In the pre-stage II patient, there is increased afterload on an already overloaded ventricle. VR is easily compromised by the increased intra-abdominal pressures and retractors. Additionally there is diminished PBF from the effects of laparoscope (secondary to increased PVR). In the Glenn patient, there is still just one ventricle but the ventricle is less volume loaded. There can be compromised VR but there is some evidence that with insufflation circulation is shifted to upper compartment preserving PBF.

Transfusion Limbo – How low will you (safely) go?

In the second lecture, Dr. Nina A. Guzzetta (Emory University) reviewed benefits and risks of RBC transfusion, indications and recent evidence for transfusion targets and triggers.

She began the talk using three illustrative cases which later informed the discussion. These were a three year old with a history of a truncus arteriosus repair with residual significant RVOT obstruction suffering a GI bleed with a hematocrit (Hct) of 17.3; a 12 year old status post repair of idiopathic scoliosis, stable in PACU with a Hct of 21.9; and a 3 week old status post Norwood-Sano undergoing a laparoscopic Nissen with SpO2 of 80% on RA and a Hct of 34.8.

Dr. Guzzetta reviewed recent transfusion trends which not surprisingly showed an increase in all the countries studied, she went on to relay data on the significant cost associated with acquiring blood and blood transfusion. Such considerations demonstrate what a valuable resource RBCs are and that given the prevalence of RBC transfusion in the perioperative setting, anesthesiologist drive many of the transfusions that occur in our respective hospitals.

Benefits of RBC transfusion were reviewed which include increasing oxygen carrying capacity and ultimately tissue oxygenation, and hemostasis. Looking firstly at increasing oxygen carrying capacity and what the critical value for oxygen delivery is, a study was reviewed involving healthy adult volunteers and found that cognitive function was not impacted until a Hgb value of 5.7 g/dL was reached by isovolemic hemodilution. Such data isn’t easily transferrable to pediatric patients given several reasons.

A study looking at older healthy children undergoing scoliosis surgery found that it wasn’t until a Hgb value of 3.0 g/dL was reached that there were significant hemodynamic changes. Such studies, while informative don’t answer the question of what the critical Hgb value in a critically ill child with poor cardiac reserve is.

Regarding tissue oxygenation, two conditions where increased oxygen-carrying capacity does not necessarily increase tissue oxygenation were discussed, namely sepsis and what Dr. Guzzetta referred to as the ‘storage lesion’ – where stored RBCs may not deliver sufficient oxygen given a decrease in the quality and quantity of the RBCs. Two studies which demonstrated worse outcomes associated with transfusion of older units of PRBCs were then reviewed. Finally with regards to the beneficial effect of RBC transfusion Dr. Guzzetta discussed the rheological effects of RBCs that help promote platelet-endothelial interaction and ultimately platelet activation.

The discussion moved to risks associated with transfusion of RBCs; a graph was displayed showing that the biggest risk was inappropriate blood component transfusion (composed of both lab errors and clinical errors), the second largest risk was acute transfusion reaction. Data was then displayed demonstrating that transfusion risks are actually higher in pediatric patients (as compared to adults) highlighting the need for caution when transfusing blood components. Immune-mediated risks (alloimmunization, hemolytic transfusion reactions, TRALI) versus nonimmune-mediated risks (volume overload, metabolic derangements, and NEC) were touched upon.

Dr. Guzzetta went on to discuss transfusion triggers. Starting with STS/SCA practice guidelines, recommendations in adults include transfusing for a Hgb value of less than 6 g/dL, for a value of less than 7 g/dL in the postoperative patient and for a value of less than 10 g/dL in the patient with end-organ ischemia. In pediatric patients guidelines from the British Journal of Haematology exist suggesting a transfusion trigger of 10 g/dL if the patient has chronic oxygen dependency or a trigger of 12 g/dL in the case of a neonate requiring ICU care.

These guidelines have been updated for neonates as follows: if the neonate is greater than a week of age and without an oxygen requirement a Hgb value down to 7.5 g/dL is acceptable. If the neonate is on oxygen or CPAP a Hgb value down to 10 g/dL (if less than 1 week of age) or 9 g/dL (if greater than 1 week of age) is acceptable. Finally for ventilated patients less than 1 week of age, Hgb should be maintained at greater than 12 g/dL while in those greater than 1 week of age, a Hgb of 11 g/dL or greater is acceptable. In patients with congenital cyanotic heart disease it is recommended that the Hgb be maintained between 14-18 g/dL.

Several studies were reviewed to gain an understanding of where the above guidelines were derived from. Dr. Guzzetta also went on to consider the specific example of Hct and low flow CPB citing a study suggesting that cerebral microcirculation and neurodevelopmental outcomes are better when the Hct is maintained at a value of 30% as compared to a value of 20%.

The lecture concluded with the admonishment that more prospective randomized trials were needed to help elucidate the differences in transfusion triggers in the preterm vs. the neonate vs. older infants and children vs. the child with congenital cyanotic heart disease.

Sunday CRNA Symposium

Reviewed by Christelle Poulin-Harnois, MD

Seattle Children’s Hospital

Seattle, WA

In the first session titled “Brain Damage in the OR: Anesthesia and Neurotoxicity”,

Dr. Andreas W. Loepke (Cincinnati Children’s, Cincinnati) discussed the latest evidence behind anesthesia and neurotoxicity. More than 300 articles describe neuronal apoptosis in animal models. Apoptosis is a normal part of brain development but anesthesia seem to disturb this process. When multiple anesthetics are combined, a more definite apoptotic pattern is seen. Furthermore, architectural changes in the brain occur secondary to anesthetics. Propofol affects dendritic formation, but interestingly its effect differs depending on the age of the neuron. Also, anesthesia seems to reduce the number of synapses.

Looking at different cohort studies, anesthesia seems to be associated with learning disabilities and changes in language and cognition. There might be a genetic predisposition. However, one must keep in mind that it is impossible to differentiate the effects from surgery, pain and anesthesia versus the initial reason for requiring surgery. Previous studies demonstrate that inadequate treatment of pain is associated with altered pain responses and impairment in cognitive and motor development. In animals, administration of ketamine prior to painful stimuli decreases apoptosis compared to each one alone. Neurons seem to be more susceptible during their growth spurt, which occurs in humans below age 4. Anesthetics with GABA or NMDA receptor mediated effect seem to have the most deleterious effects for the brain.

Future strategies to ameliorate anesthesia induced cell death include drugs such as estradiol, melatonin, pilocarpin, lithium, xenon, isoflurane preconditioning, and dexmetomidine as well as hypothermia. Dexmetomidine, given alone or with other anesthetics, may decrease apoptosis. His take home message was to minimize sedative, drug doses and exposure time. Regional anesthesia should be considered as a tool to decrease anesthetic exposure. However one must keep in mind that very little research has been done in humans, thus more research is needed.

For the second session, “Before they’re born: Anesthesia for Fetal Surgery”,

Joan Beiersdorfer, CRNA, MSN (Cincinnati Children’s, Cincinnati) presented a review on anesthesia for fetal surgery. There are 4 millions births in the US per year and 3% or 120,000 will have complex birth defects. Fetal surgery attempts to improve outcomes for some with in-utero treatment before a debilitating defect occurs. Women who are candidates for these surgeries are healthy ASA I or II without any pregnancy-related complications. Usual considerations for pregnant patients were reviewed. Fetal onsideration include immature cardiac function, altered pharmacokinetics, risk of hypothermia, low circulating blood volume.

Fetuses seem to feel pain in the 2nd trimester. The most important aspect of anesthesia for fetal surgery is utero-placental blood flow. Uterine blood flow is directly related to uterine perfusion pressure and inversely related to uterine vascular resistance. Remember that maintaining stable maternal hemodynamics and stable EtO2 help maintain good uterine perfusion. Most drugs cross the placenta except for glycopyrolate, insulin, heparin and all paralytics.

The major perioperative considerations for fetal surgery are:

- maintain blood pressure within 10% of normal value

- limit crystalloid use to 1L (risk of pulmonary edema for mother), use vasoactive drugs

- Keep mother and fetus warm

- Avoid uterine contraction (available tocolytics)

- Monitor mother and fetus

- Have resuscitation team for fetus available

Three types of fetal surgery were addressed: minimally invasive, open fetal surgery and EXIT procedure. Minimally invasive surgeries are performed under monitored anesthesia care. Open procedures and EXIT procedures usually involve a RSI/epidural, arterial line, 2 large bore IVs for the mother. IM injections of drugs for the fetus are prepared and include epinephrine 10 mcg/kg, atropine 20mcg/kg, vecuronium 0.2 mg/kg and fentanyl 10mcg/kg. Continuous fetal echo is performed during the procedure. Methods to maintain uterine relaxation include high desflurane, nitroglycerin and magnesium. A balanced anesthetic using propofol, remifentanil and desflurane is one way of achieving these goals .

Possible complications include fetal demise and pre-term labour (PTL). After an open mid-gestation procedure, mothers are usually required to maintain bed rest to prevent PTL. EXIT procedures are used when fetuses have anomalies that require immediate securing of the airway or initiation of ECMO. Open procedure are used for myelomeningocele, sacral teratoma, etc.

For the third session, “Born blue: Anesthesia for congenital heart disease”,