Clinical Review

Noonan Syndrome: Clinical Features and Considerations for Anesthetic Management

Justin D. Ramos, MD

Pediatric Anesthesiology Fellow

Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine

Oregon Health & Science University

Portland, Oregon

ramosju@ohsu.edu

Dean Laochamroonvorapongse, MD MPH

Assistant Professor

Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine

Oregon Health & Science University

Portland, Oregon

laochamr@ohsu.edu

Introduction

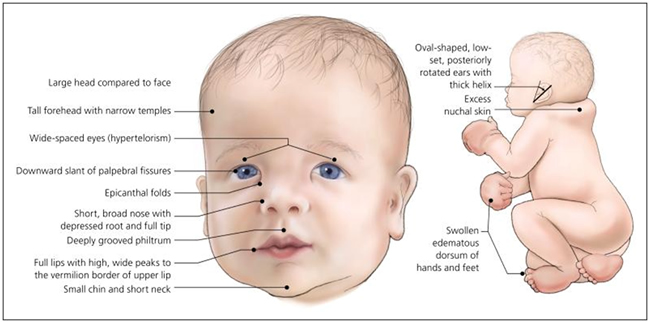

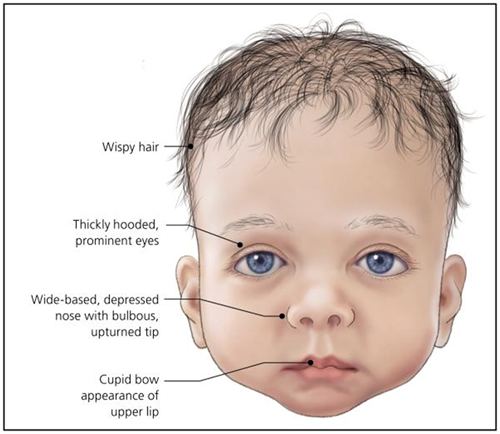

Noonan Syndrome is a common genetic disorder characterized by distinctive facial features, webbing of the neck, sternal deformities, short stature, congenital heart disease, hematologic abnormalities, variable developmental delay, cryptorchidism and lymphatic abnormalities. The distinctive facial features include wide spaced eyes (hypertelorism), downward slanting palpebral fissures, short broad nose, deeply grooved philtrum, low-set posteriorly rotated ears and excess nuchal skin (Figures 1 and 2). Noonan syndrome exhibits autosomal dominant inheritance, although a majority (up to 60%) of cases arise from spontaneous mutations.

Pediatric anesthesiologists are likely to encounter patients with Noonan Syndrome, as the incidence of the syndrome may be as common as 1:1000 live births, and it is the second most common syndromic cause of congenital heart disease after Down’s syndrome. This review will provide an overview of clinical features of Noonan Syndrome and how they impact anesthetic management.

Figure 1 – A newborn with features of Noonan Syndrome

(Bhambhani V, Muenke M. Noonan syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(1):37-43)

Figure 2 – An infant with typical features of Noonan syndrome.

(Bhambhani V, Muenke M. Noonan syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(1):37-43)

Epidemiology

The incidence of Noonan Syndrome is estimated to be between 1:1000 and 1:2500 live births. Due to highly variable expressivity, many mildly affected individuals may go undiagnosed into adulthood or until they have more prominently affected children. There is no known association with race or sex. Diagnosis is typically made by clinical features, but genetic testing can now confirm up to 70% of cases.

Pathophysiology

Patients with Noonan Syndrome have a normal karyotype. However, the most common genetic mutation is found in the protein tyrosine phosphatase nonreceptor, type 11 gene (PTPN 11), which accounts for about half of all cases. The PTPN 11 mutation and other mutations that cause Noonan Syndrome predominantly alter genes in the RAS-mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway which affects how extracellular ligands like growth factors, cytokines, and hormones exert their effects on cellular functions.

Diagnosis

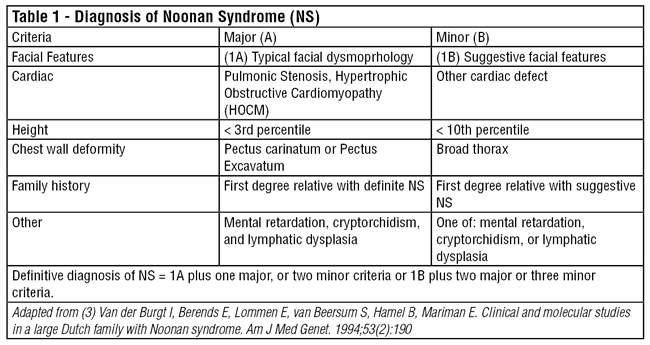

As genetic molecular analysis can only confirm 60-75% of cases at this time, accurate clinical diagnosis of Noonan syndrome is important for identifying affected individuals who will need comprehensive medical care throughout their lives. Van der Burgt et. al proposed clinical diagnostic criteria for Noonan syndrome (Table 1). Definitive Noonan Syndrome is considered the presence of typical facial dysmorphology with one other major criteria or two minor criteria. If the facial dysmorphology is only suggestive, then two major criteria or three minor criteria must also be present to make the diagnosis. The distinctive facial features of the syndrome include hypertelorism, downward slanting palpebral fissures, short broad nose, deeply grooved philtrum, low-set posteriorly rotated ears and excess nuchal skin (see Figure 1).

Some phenotypically similar conditions, that may have overlapping features with Noonan Syndrome include Turner Syndrome (45X Karyotype), Cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome, Legius syndrome, Costello syndrome, Neurofibromatosis Type 1, and Noonan Syndrome with multiple Lentigines (formerly called LEOPARD syndrome for Lentigines, ECG abnormalities, Ocular hypertelorism, Pulmonary stenosis, Abnormal genitalia, Retardation of growth and sensorineural Deafness). Many of the related disorders also have genetic mutations within the RAS pathways and are collectively deemed Rasopathies.

Clinical Features and Anesthetic Considerations

Cardiovascular

Congenital heart disease is very common in Noonan syndrome; up to 80% of patients have some form of cardiac abnormality. Pulmonic stenosis is the most common abnormality (50-60%) and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is also fairly common (20%). Atrial septal defects (ASD) occur in 6-10% of patients, and Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD), AV Canal, valvular abnormalities, coarctation and abnormal coronary implantation are possible. ECG abnormalities at baseline are also common.

All patients with Noonan syndrome should have an echocardiogram and lifelong cardiology follow-up. One third of patients with pulmonic stenosis will require surgical repair, but patients with varying degrees of pulmonic stenosis may present for non-cardiac surgery. If pulmonic stenosis is significant, patients may have varying degrees of right ventricular (RV) hypertrophy, with a component RV dysfunction. Careful attention should be paid to maintaining adequate preload for a thickened RV with decreased chamber size and potential diastolic dysfunction, but fluid overload should also be avoided especially if there is RV systolic dysfunction. Ventilation must be carefully managed so as to avoid hypoxia, hypercarbia, or high peak airway pressures that may exacerbate pulmonary hypertension and increase RV strain.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is the second most common congenital cardiac disease in Noonan syndrome patients (20%). Although Noonan patients exhibit a lower incidence of sudden cardiac death from arrhythmias than in patients with isolated congenital hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM), the overall mortality is similar due to heart failure is similar. Management of these Noonan syndrome patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is similar to other patients with dynamic left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction. Goals include volume management for maintaining adequate preload, avoidance of tachycardia, and maintenance of afterload in order to prevent exacerbation of dynamic LVOT obstruction. For major surgery or severe disease, invasive monitoring should be considered.

Airway and Pulmonary

Due to airway abnormalities, some Noonan patients may be a difficult laryngoscopy. Patients should be screened for a history of difficult intubation, and careful preoperative airway assessment should be performed in order to assess the potential for difficult intubation. Abnormalities such as a short or severely webbed neck, micrognathia, dental malocclusion or jaw articulation problems may make direct laryngoscopy or intubation difficult in certain patients. Difficult airway equipment should be readily available, and fiberoptic intubation may be necessary.

Pectus carinatum or excavatum is a common feature, and some patients may have concurrent scoliosis. In certain patients, pulmonary function is impaired by significant chest abnormalities or scoliosis and patients should be screened by history for pulmonary symptoms.

GI, Renal and Genitourinary

Neonates and infants frequently have feeding difficulties, reflux, recurrent vomiting, and failure to thrive. Many infants may need temporary feeding tubes. Assess the patient’s reflux history and consider if high aspiration risk may warrant a rapid sequence induction. These issues usually stabilize as the patient matures.

Cryptorchidism is very common (80%) and most male patients will present for orchiopexy. Gonadal dysfunction is also common in males, though reproductive capability is typically normal in female patients. Roughly 10% of patients have some form of renal abnormality, though these rarely require treatment.

Hematologic

Hematologic and coagulation defects are common. Monocytosis, thrombocytopenia, and myeloproliferative disorders may be present. Prior to surgery, it is important to assess for any history of abnormal bruising or bleeding (up to 65% of patients) and to obtain a CBC with differential and coagulation studies. Forty percent of patients may have prolonged PTT, and up to a third of patients had factor deficiencies or platelet defects. Consider hematology consultation prior to surgery in the setting of abnormal coagulation studies or a history of abnormal bleeding. The patient’s coagulation profile should be carefully considered prior to performing regional or neuraxial anesthesia.

Psychologic and Developmental

A majority of patients have normal intelligence, though the incidence of cognitive developmental delay, learning disabilities, and need for special education programs during childhood are higher than the general population. Though birth height and weight are normal, puberty is typically delayed, which contributes to short stature when compared to similar age peers. Despite this, many patients reach normal height as adults. Growth hormone (GH) therapy is approved for use in Noonan syndrome patients due to GH deficiencies and some insulin-like growth factor (IGF) deficiencies with normal GH levels. Patients are also prone to mood disorders, such as depression, anxiety and body image disorders.

Malignant Hyperthermia Risk

Noonan syndrome patients are typically not considered to be at elevated risk for malignant hyperthermia (MH) according to most modern case series and the resources provided by the Malignant Hyperthermia Association of the United States (MHAUS). Patients with a distinct diagnosis of “Noonan-like syndrome” (SHOC2 S2G mutation) who have loose anagen hair, myopathy, normal to moderately elevated CK levels and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy may be at elevated risk for MH, so a non-triggering anesthetic should be administered to this subset of patients.

Summary

Due to a relatively high prevalence as a genetic disease and improving clinical awareness and molecular genetic diagnostic capabilities, pediatric anesthesiologists are likely to encounter patients with the diagnosis of Noonan syndrome during their careers. Patients may present for common procedures such as orchiopexy, dental surgeries, orthopedic and spine surgeries, in addition to repairs of congenital cardiac disease. Adults with Noonan syndrome will also present for surgeries throughout their lifetime. Anesthesiologists must carefully consider the presence of cardiac disease, the potentially difficult airway, and high incidence of hematologic abnormalities when planning the anesthetic management of these unique patients.

References

- Asahi Y, Fujii R, Usui N, Kagamiuchi H, Omichi S, Kotani J. Repeated General Anesthesia in a Patient With Noonan Syndrome. Anesthesia Progress. 2015;62(2):71-73. doi:10.2344/0003-3006-62.1.71.

- Bajwa SJ, Gupta S, Kaur J, et al. Anesthetic considerations and difficult airway management in a case of Noonan syndrome. Saudi J Anaesth. 2011;5(3):345-7.

- Bhambhani V, Muenke M. Noonan syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(1):37-43.

- Campbell AM, Bousfield JD. Anaesthesia in a patient with Noonan's syndrome and cardiomyopathy. Anaesthesia. 1992;47(2):131-3.

- Kruszka P, Porras AR, Addissie YA, et al. Cover Image, Volume 173A, Number 9, September 2017. Am J Med Genet A. 2017;173(9):i.

- Noonan Syndrome. In: Bissonnette B, Luginbuehl I, Marciniak B, Dalens BJ. eds. Syndromes: Rapid Recognition and Perioperative Implications New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2006. http://accessanesthesiology.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=852§ionid=49518014. Accessed November 12, 2017.

- Roberts AE, Allanson JE, Tartaglia M, Gelb BD. Noonan syndrome. The Lancet. 2013;381(9863):333-342.

- Romano AA, Allanson JE, Dahlgren J, et al. Noonan syndrome: clinical features, diagnosis, and management guidelines. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):746-59.

- Shaw R, Weintraub A, Litman R. Does Noonan Syndrome Increase Malignant Hyperthermia Susceptibility? https://www.mhaus.org/healthcare-professionals/mhaus-recommendations/does-noonan-syndrome-increase-malignant-hyperthermia-susceptibility/.

- Tartaglia M, Gelb BD, Zenker M. Noonan syndrome and clinically related disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;25(1):161-79.

- Turner AM. Noonan syndrome. J Paediatr Child Health. 2014;50(10):E14-20.

- Van der Burgt I, Berends E, Lommen E, van Beersum S, Hamel B, Mariman E. Clinical and molecular studies in a large Dutch family with Noonan syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1994;53(2):190

- Van der Burgt I. Noonan syndrome. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 2007;2:4. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-4.