SPACIES

A Day in My Life: Tales from two trainees

By Faye M. Evans, MD

Boston Children’s Hospital

Chair, Society for Pediatric Anesthesia’s Committee on International Education and Service (SPACIES)

There is growing evidence to indicate that the current generation of medical students and young physicians are very interested in and committed to global health.1 This interest has been paralleled by an increase in opportunities for both medical students and residents to be exposed and become involved in global health at earlier stages within their career. In fact, many residency programs such as pediatrics, general surgery, emergency medicine, internal medicine, family medicine, and anesthesiology offer international electives or global health tracks within their curricula.2-7

In this edition of the SPA newsletter we are fortunate to share two personal views from anesthesia trainees describing their personal experiences working in the low resource setting. The first is from Dr. Nancy Okonu who is a pediatric anesthesia fellow at the University of Nairobi who poignantly describes her experiences as a pediatric anesthesia fellow in Kenya and the challenges she faces every day trying to take care of very sick children. The second is from Dr. Tabish Hoda who completed a rotation as an anesthesia resident at Temple University. In his personal view, he describes his first experience working in the low resource setting and the impact it has had on his career as an anesthesiologist.

My Experience as a Fellow in Paediatric Anaesthesia at the University of Nairobi

Dr. Nancy Okonu

Paediatric Anaesthesia Fellow

University of Nairobi

The Paediatric Anesthesia fellowship is a relatively new programme at the University of Nairobi and is supported by a collaboration of several organizations including The World Federation of Societies of Anesthesiologists (WFSA) and the Society for Pediatric Anesthesia (SPA). The first class has just completed their programme. I am more than privileged to be in the second class. We reported to the University of Nairobi in September 2014, and were welcomed by Dr. Mark Gacii who is the head of the programme.

University of Nairobi Pediatric Anesthesia Fellows 2014-15: Dr. Allan Chochi, Dr. Nancy Okonu, and Dr. Christopher Chanda

It is now five months later and it has been quite an experience I must say. With great instructors in Paediatric anaesthesia there has been great learning. There are daily surgical lists and the days can sometimes be quite long and exhausting but stimulating and challenging as well. The case mixes are also quite interesting. For some of us, who are from smaller rural hospitals, this has been especially interesting.

We rotate through various clinical areas at Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH) including theatre, ICU, NICU, and at Kijabe Hospital. My very first rotation was ICU and this was baptism by fire to say the least. I had already studied at the University of Nairobi for both my undergraduate and post-graduate education, and I thought this would not be so hard as I was already familiar with the system. Well familiarity could not save me on my first day in ICU.

The ICU was running but there were no doctors as the residents were on a “go slow.” I met one of my senior colleagues and the greeting was “Oh thank God you are here. Start on the other side.” I asked, “Who am I working with?” and he said, “no one you are on your own. “There is no hand over report, just start off.” So I started off, no hand over, starting to read charts of which some had five volumes of files. I had been out of KNH for two years and much had changed from even the basics of laboratory request forms. Luckily the nurses were really helpful. Thus far that has been both my shortest and longest day in this programme all at the same time. Short because I soon realized it was 5 pm and I was to hand over to the night team and long because I had not taken a tea, lunch or bathroom break. As I stepped out of ICU that evening, I shuddered at the thought of what the rest of the training will be like if this was only the first day.

Soon after that we had training on Emergency Triage Assessment and Treatment (ETAT) on emergency paediatric care in Kenya, which was fantastic. It was interesting relearning how to fix an intraosseous cannula on a chicken bone. Then the theatre rotations soon were the order of the day. There has been a great mix of cases and excellent hands on experience. Some cases are quite challenging, but thank God we are always with the Paediatric Anaesthesiologists.

The weekend calls are especially good learning experiences. The Paediatric anesthesia fellows are responsible for running the lists although occasionally, our instructors do join us. These are the days you make independent decisions but you can always consult one of your Attendings. We are also joined by a resident who we are responsible for teaching as we work together. Most cases are emergencies or urgent cases. The patients are usually quite sick and not well stabilized for surgery.

My first call was quite long as I left the theatre at 4 am and lost one child on the theatre table. This was quite devastating. I was back to theatre at 9 am the following morning for another day. How I wished there was a debriefing after such an incident. But life must go on, you can’t keep whining, toughen up my friend as this is anaesthesia and is not for the faint hearted. That is how I encourage myself.

My worst nightmare is children requiring peritoneal dialysis (PD) catheter insertions and those requiring central venous catheters (CVCs). The PD catheter patients are typically quite sick with renal function derangement and they often come to theatre late. The PD catheters are not available at KNH and they are very costly for the family to purchase. By the time the relatives gather enough money to buy the catheter the child will have really deteriorated. Some of these children come to theatre already gasping making the choice of anesthesia really challenging. I used to feel like running away from theatre when I knew the next case was a PD catheter insertion but not anymore. A couple of times I have removed some PD catheter after dialysis so it is not always gloom and hopelessness.

As for the CVCs, these are also unavailable at KNH, which is a nightmare. In addition, they are very costly to the patient’s family. I always start off placement of a CVC knowing there is zero chance for failure. This is my prayer, Oh God you know this baby’s family has bought only this one CVC and I must get it right, Oh help me God. There are times that I fail and need to consult the Attending Paediatric Anaesthesiologist for assistance. Sometimes it takes over two hours to place one. Being a blind procedure, the risk of complications are always high. I keep praying that one day I will not only learn to place CVCs via ultrasound guidance, but also have one in the hospital to use at any time.

My Kijabe hospital rotation was amazing. This is a hospital in the middle of nowhere with a beautiful and serene environment. Dr. Mark Newton was quite welcoming and a great teacher. The hospital is strikingly organized and quite efficient. It is well organized and therefore seems less resource constrained than KNH. The staff is quite friendly and very prayerful too. The nurse anaesthesia training is also great. My experience was wonderful and I look forward to going back there soon.

Unfortunately the NICU rotation is really not very strong with terrible outcomes and mortality being so common. I hope this improves with the current ongoing efforts to build capacity through training.

We hope for better resources as we do our best with what is available to offer anaesthesia services to our children.

My Experience as a Visiting Resident at the Cure Hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Tabish Hoda, DO

Anesthesia Resident

Temple University Hospital

The international rotation in Ethiopia was recommended to me by a few of my fellow residents who had told me they had exceptional educational benefit from it. Having heard many positive reviews of their unique experiences, I decided to communicate with Dr. Drum, the coordinator for the Temple University Anesthesia International rotation. She prepped me on what to expect and how to prepare for the rotation. After all the arrangements had been made, I departed to Ethiopia for about a week.

Once in Ethiopia, I met with the rest of the medical team from the US. The team was composed of ENT surgeons, ENT residents, audiologists, RNs, and a medical trip coordinator. Dr. Drum and I were the only members of the anesthesiology team.

My first few days there were spent at CURE, a pediatric hospital that is widely recognized as one of the most advanced hospitals in Ethiopia. I began to learn the dynamics of anesthesia services in Ethiopia. I learned that majority of the anesthetics in the country were independently provided by non-physician anesthetists that had gone to an anesthesia school, post high school graduation. They were not physicians or nurses. Majority of them had an equivalent of what would be considered a four-year college degree in the US. According to Dr. Mary, who was the only attending anesthesiologist at the hospital, the anesthesia students at CURE were already certified anesthetists that had come there to further their skills and education, and earn an equivalent of a Masters degree in Anesthesia. In speaking to some of the students, I learned anesthetists with Masters degrees are highly regarded and sought after in Ethiopia, and CURE was one of the only programs available in the country for them to further their training. I had the opportunity to teach the students, give lectures, and observe their practice of anesthesia.

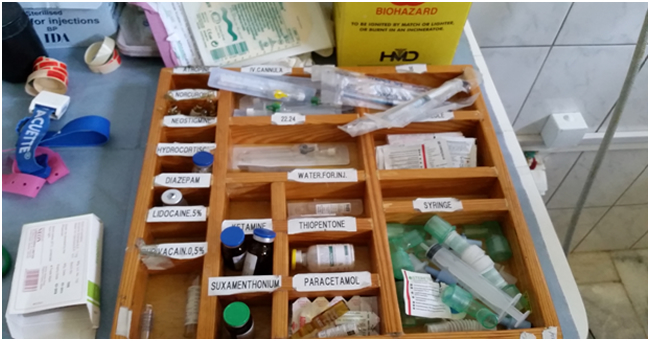

At CURE, I noted numerous differences from our standard of practice in the US. Many of the things I observed were quite fascinating to me. There were no oxygen pipelines, or wall O2 supply. Each OR was equipped with an H cylinder that had to be periodically refilled. There was no nitrous oxide or air available. Pharmacological choices were also quite limited due to expenses and availability. Neuromuscular blocking drugs were rarely used to facilitate intubation unless absolutely indicated. Narcotics were used very conservatively to contain costs.

ETT, laryngoscopes, and oral airways were all washed and reused. There were no video scopes to assist with difficult intubations. The surgical drapes were cloth, and were also washed and reused. All of the operating rooms had large windows since there was no back up power supply in case of power failure. Hypotension was often undertreated since availability of vasopressors such as phenylephrine or ephedrine was scarce. The PACU did not have oxygen tanks, but only had oxygen concentrators (something that was foreign to me). I learned that the highest FiO2 deliverable via a concentrator was 50%. This was all quite a transition in practice for me, as I was not used to working with limited resources or putting a strong emphasis on cost containment.

O2 Concentrator

H Cylinder

Rear of Anesthesia machine

Once I had started to become acclimated to the way anesthesia was practiced at CURE hospital, Dr. Drum felt it was necessary for me to move on to see the other hospitals in the city. CURE was considered the most advanced hospital and limiting my experience exclusively to CURE would give me a skewed perspective on anesthesia practice in Ethiopia. I prepared for my trip to St. Paul hospital and Yekatit 12 (another pediatric hospital). Dr. Drum gave me a bag full of anesthesia supplies in case it was unavailable or malfunctioned (which was relatively frequent) while at the hospitals. I was equipped with a portable pulse oximeter, capnograph, blood pressure cuff, laryngoscopes, laryngeal mask airways, oral and nasal airways, and emergency drugs. I traveled to Yekatit 12 with Dr. Mary, the attending anesthesiologist from CURE hospital. Once at Yekatit 12, I was taken aback by the lack of tools we had to work with. To name a few striking observations, I realized the drug selection was extremely limited. The overhead OR lights did not work. There were no warming blankets for the patients. What was most shocking to me was we used a portable electric heater to try to keep our patient (a two year old infant) warm. Yekatit 12 started to give me a real taste of what it is like to practice anesthesia in Ethiopia.

Our medication selection

Electric space heater

Once we had completed our procedures for the day at Yekatit 12, I departed for St. Paul hospital to meet with Dr. Jay, an ENT surgeon. St. Paul hospital is a large trauma center and a tertiary referral center in Addis Ababa. We had an Endoscopic sinus surgery scheduled on an elder male. On arrival, I started to study my surroundings and familiarize myself with the equipment that we had available. I was told there was no attending anesthesiologist present in the hospital that day and the only anesthesia providers were the anesthetists. I was shocked to learn that there were no oral airways, no nasal airways, no LMA, no video scope or fiberoptic scopes.

In the case of a difficult airway in which we could not ventilate or intubate, the only option would be to urgently obtain a surgical airway. Luckily, I had brought with me the bag of anesthesia supplies provided by Dr. Drum to attenuate the uneasy feeling I wasn’t quite acquainted with. We induced anesthesia with thiopental exclusively and maintained anesthesia with halothane and used morphine for analgesia. The intra-operative course was complicated with moderate to severe hypotension. The only available pharmacologic option to manage the hypotension was epinephrine. However, in observing the anesthetists I realized that they did not see the significance of increasing our patient’s blood pressure and would normally leave it untreated. I took this opportunity to teach about the complications that may arise if significant hypotension is not treated, especially on an elderly patient. We diluted the 1:1000 vial of epinephrine and slowly dripped it IVPB since there was no infusion pump. The rest of the case was uneventful and there were no complications during emergence. In speaking to some of the surgeons, I learned that they felt that peri-operative morbidity and mortality secondary to anesthesia related causes was quite common. However, the accuracy of their sentiments were unable to be delineated since there were not any electronic records, and paper records were often unreliable and difficult to obtain.

The trip to Ethiopia was truly enlightening for me. It opened up my eyes to the level of anesthesia services provided, and several of its shortcomings in many parts of the world. Completing my residency training in 2015, I would not have been able to really comprehend what it is like to provide anesthesia with such limited resources or have had the opportunity to use drugs such as thiopental and halothane.

Many of the things we take for granted daily in the US are considered luxuries that anesthesia providers in other parts of the world may have only read about in books. I took advantage of every opportunity to teach and learn. I was able to witness firsthand how socioeconomic factors in other parts of the world strongly impact the level and quality of medical care provided. All of these observations inspired me to study the history and development of anesthesia as a science, the inventions of what we now consider standard ASA monitors, advancements in pharmacology and physics, and growth of anesthesia into a full fledged medical profession over the last two centuries in the US.

We are fortunate to have the plethora of resources and knowledge available to us here in the US, and I feel it is important that we become involved in trying to help grow our profession at a global level, especially in those areas most in need. Although anesthetists in Ethiopia often have a wealth of clinical experience and are technically skilled, their limited training in the application of pharmacology, physiology, and the principles behind anesthesia practice is at times a constraint in providing optimal anesthesia care. It was apparent that there is insufficient physician staff to educate and supervise anesthetists, or support residency training programs.

There are only 12 practicing anesthesiologists and one residency training program in Ethiopia, a country with a population of about 80 million people. In comparison, Pennsylvania has about 1900 anesthesiologists and a population of 15 million people. During my entire stay, I only met only one staff anesthesiologist based at CURE hospital. Accurate account of mortality and morbidity related to anesthesia is limited by the paucity of available data regarding surgical care, infrastructure, human resources, and lack of access to reliable intra-operative records.

I am currently working with Dr. Drum to initiate a prospective study on peri-operative mortality related to anesthesia by advocating the implementation of basic QA forms into official anesthesia records at hospitals willing to participate in Addis Ababa. With reliable data and accountability, we can hopefully focus on weaknesses in the healthcare system and put effort into advocating for improved infrastructure, education, and training. It is imperative that we support well-designed teaching efforts in countries like Ethiopia. Without our help, it would be extremely difficult for the few anesthesiologists in Ethiopia to adequately train enough residents and have a profound impact on improving the quality of anesthesia care. I highly recommend that all residents in the US have the opportunity to do an international rotation, as my experience has been profoundly invaluable.

References

- Panosian C, Coates TJ. The new medical “missionaries--”grooming the next generation of global health workers. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(17):1771-1773. doi:10.1056/NEJMp068035.

- McCunn M, Speck RM, Chung I, Atkins JH, Raiten JM, Fleisher LA. Global health outreach during anesthesiology residency in the United States: a survey of interest, barriers to participation, and proposed solutions. J Clin Anesth. 2012;24(1):38-43. doi:10.1016/j.jclinane.2011.06.007.

- Nelson BD, Lee AC, Newby PK, Chamberlin MR, Huang C-C. Global health training in pediatric residency programs. PEDIATRICS. 2008;122(1):28-33. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-2178.

- Suchdev PS, Shah A, Derby KS, et al. A proposed model curriculum in global child health for pediatric residents. Acad Pediatr. 2012;12(3):229-237. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2012.02.003.

- Jayaraman SP, Ayzengart AL, Goetz LH, Ozgediz D, Farmer DL. Global Health in General Surgery Residency: A National Survey. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2009;208(3):426-433. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.11.014.

- Morton MJ, Vu A. International emergency medicine and global health: training and career paths for emergency medicine residents. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57(5):520-525. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.050.

- Furin JJ, Farmer P, Wolf M, et al. Project MUSE - A Novel Training Model to Address Health Problems in Poor and Underserved Populations. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2006. doi:10.1353/hpu.2006.0023.