Pediatric Anesthesiology 2018 Reviews

Saturday Session II: Small Patient, Smaller Incision, Big Problems

Reviewed by Chris D. Glover, MD, MBA

Reviewed by Chris D. Glover, MD, MBA

Texas Children’s Hospital

This review provides a synopsis of Session II: Small Patient, Smaller Incision, Big Problems. The initial lecture by Dr. Katherine Barsness (Lurie Children’s Hospital, Chicago) provided the surgical perspective for minimally invasive surgery in neonates. The themes of her discussion included: the neonatal congenital conditions amenable to minimally invasive surgical (MIS) repair, physiologic changes commonly encountered during MIS, and team processes necessary to ensure optimal outcomes in this patient population.

The advent of thoracoscopic cases in neonates begs the question on efficacy or improved outcomes when compared to open methods. Dr. Barsness emphasized that while MIS does not necessarily change the goals of the procedure, it does confer benefit in specific neonatal conditions. But along with those benefits, MIS can create challenges for both surgeons and anesthesiologists in the care of critically ill neonates.

While MIS has evolved as a technique for use in multiple procedures, Dr. Barsness focused her discussion on MIS for esophageal atresia and diaphragmatic hernia. In those children with esophageal atresia – reported indications were a weight >1.4 kg. This lower weight limit can vary by surgeon.

Contraindications include:

- Hypoplastic heart disease

- Intubated patients with poor oxygenation

- Children with distended abdomens

- Those unable to tolerate positioning for this procedure.

There should be awareness on how hypermobile the mediastinum is in neonates, especially in conjunction with classic positioning in the lateral position to repair esophageal atresia. Initiation of insufflation commonly results in a worsening of the V/Q mismatch with significant and prolonged desaturations. To mitigate this hypermobility and associated ventilation issues, Dr. Barsness reported on her center’s experience in treating esophageal atresia with MIS in the prone position.

While there can be issues with access to the stomach or selective ventilation in the prone position, Dr. Barsness emphasized the improvement noted in response to insufflation as well as a quicker resolution of the aforementioned V/Q mismatch that occurs.

For the approach in a neonate with congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH), Dr. Barsness pointed to specific clinical indicators that would make the open approach a more appropriate consideration. They include:

- If >50% of the diaphragm was missing on imaging.

- Being unstable in the NICU or being unstable on transport.

- Becoming unstable with insufflation.

Given the lung hypoplasia inherent in CDH, positioning children for this procedure is less concerning as hernia contents continue serving as a wedge mitigating lung expansion even in the lateral position. An interesting surgical technique at Lurie Children’s Hospital is the discontinuation of insufflation following bowel reduction back into the abdomen as lung hypoplasia limits significant lung expansion post reduction.

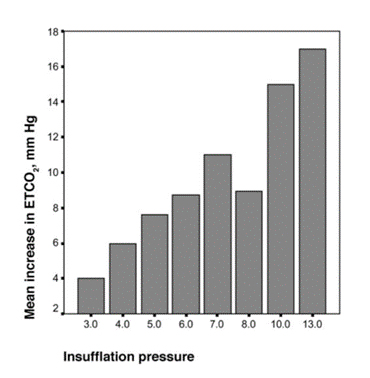

Minimizing insufflation in an effort to mitigate hypercapnea and acidosis was also discussed. She did cite a research report from Zani et al that correlated the mean increase in EtCO2 to insufflation pressures (fig 1.), but took issue with study data pointing to insufflation pressures that were twice the pressures used by neonatal MIS experts.

Fig 1. Insufflation Pressures and EtCO2 Correlation

As far as opportunities for improved success in these cases, Dr. Barsness pointed to the necessity of bidirectional communication, the use of a preinduction timeout to discuss specific intervention paths for potential adverse events, and minimizing staff turnover during these complex cases.

Abdominal laparoscopic cases were also briefly discussed with emphasis on the vigilance required for those cases given the potential for air embolism. Entrainment of air through umbilical vein / ductus venosus leads to RVOT obstruction and cardiovascular collapse. Infraumbilical incisions following the Hassan technique should be noted. While case reports describing venous air embolus exist, Dr. Barsness pointedly reminded the audience that this catastrophic complication remains under reported.

Justin Long, MD (Emory School of Medicine, Atlanta) gave the anesthesiologists’ perspective for this panel discussion with a focus on reviewing the anesthetic challenges associated with minimally invasive surgery (MIS) in the neonate. He also discussed a framework for which patients may benefit from MIS with the conclusion of the talk used to provide a synopsis of the strategies that may aid early extubation.

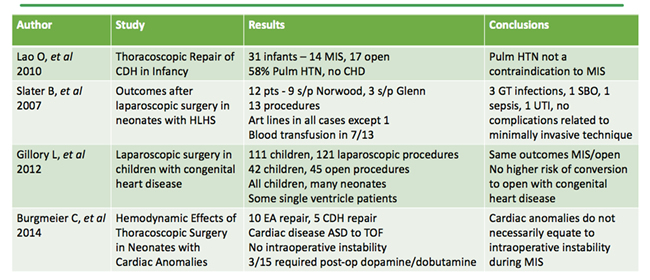

Dr. Long reported his institution’s annual rate of noncardiac neonatal cases. This accounted for roughly 1.1% of all cases performed annually pointing to the relative infrequency in which these cases present through the course of a year. A brief review of the literature fails to provide consensus on which cases are indicated for MIS repair versus not. It is surprising to note that cardiac anomalies and pulmonary hypertension do not exclude patients from undergoing minimally invasive procedures.

Table 1. Literature Review for MIS Indications

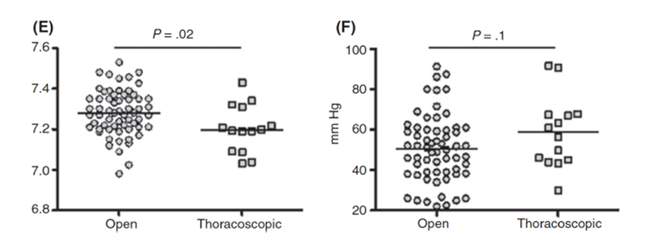

Again, an overarching clinical management dilemma centers on the physiologic derangements with insufflation. Air embolism remains an ever present in patients undergoing MIS. Standard insufflation pressures quoted in the literature by Dr. Long were 4 mm Hg in the chest and 10-12 in the abdomen. Even staying within these boundaries for cases, patients can develop significant decreases in oxygen saturation, EtCO2, and tidal volumes with significant increases in peak inspiratory pressures along with the development of acidosis when compared to open procedures (table 2). MIS procedures lasting longer than 100 minutes are particularly concerning given the associated temperature noted in the postoperative period.

Table 2. Open vs. MIS for TEF/EA – Comparison of ph and EtCO2

Dr. Long discussed the challenge of single lung ventilation specific to thoracoscopic surgery with points of emphasis on what happens with the dependent / ventilated lung blood flow with atelectasis and HPV along with potential surgical compression. For the purposes of monitoring children during these complex procedures, Dr. Long again pointed to limitations with equipment currently available. Hypotension, the correlation between paCO2 / ETCO2 remain affected given high dead space and sampling issues in the face of whatever ventilatory strategy that’s in use. Correlating these values as a trend monitor seems a better reflection per the lecture.

With regards concerning hypercapnea in this population during these procedures; Dr. Long pointed to the potential benefit of HFOV versus conventional ventilation given two studies (2,3) by whereby HFOV maintained normocarbia versus hypercapnea up to 130mmHg in patients ventilated conventionally. Even at this significant level of hypercapnea; the lowest documented oxygen saturation was 92%.

The second portion of Dr. Long’s talk provided the audience background on the benefits of multimodal anesthesia. The use of ketorolac in those <37 PCA or less than 21 days is of particular concern given the increase in bleeding risk noted in Aldrink et al.

The use of advanced regional techniques such as paravertebral catheters and epidurals has shown benefit in this patient population with noted decrease in morphine consumption and decreased length of ICU stay. While safety has been supported by PRAN data on neuraxial catheters; basing efficacy on sample sizes < 20 point to the need for continued assessment.

From an outcomes perspective, data from Chu et al paints a picture that is of concern. Mortality in those with major noncardiac anomalies approaches 5% with worse outcomes seen in children with diaphragmatic hernia and best outcomes for those with isolated gastroschisis. Specific risk factors for a poor neurodevelopmental outcome include:

- Low birth weight.

- Higher number of anomalies

- Longer LOS

- Duration of mechanical ventilation

- Supplemental oxygen at discharge

- Repeated surgery

Through both lectures, Dr. Barsness and Dr. Long provided a thoughtful framework on the physiologic issues encountered and the necessity of team based debriefing to optimize care for critically ill children undergoing MIS. Incorporation of a multimodal analgesic plan should be aggressive in treating these children. Trying to reach consensus on the suitability of children based on weight or other pre-existing comorbidities continue to provide challenges in those presenting for MIS given the potential complications associated with surgical technique.

- Zani A, et al. Intraoperative acidosis and hypercapnia during thoracoscopic repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernia and esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula. Paediatr Anaesth. 2017 Aug;27(8):841-848.

- Mortellaro VE, et al. The use of high-frequency oscillating ventilation to facilitate stability during neonatalthoracoscopic operations. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011 Nov;21(9):877-9.

- Bliss D, et al. Should intraoperative hypercapnea or hypercarbia raise concern in neonates undergoing thoracoscopic repair of diaphragmatic hernia of Bochdalek? J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009 Apr;19 Suppl 1:S55-8.

- Aldrink JH, et al. Safety of ketorolac in surgical neonates and infants 0 to 3 months old. J Pediatr Surg. 2011 Jun;46(6):1081-5.

- Chu DI, et al. Mortality and Morbidity after Laparoscopic Surgery in Children with and without Congenital Heart Disease. J Pediatr. 2017 Jun;185:88-93.